“Witnessing Perpetuity: Carlos Alfonzo,” exhibition catalogue, LnS Gallery, Miami, 2020. [Ill. 16]

CARLOS ALFONZO: TRANSFORMATIVE WORK FROM CUBA TO MIAMI AND THE U.S

“My work has to do with violence. I don’t see life as a pretty picture. It’s a very interesting picture, but not a pretty one.”[1] —Carlos Alfonzo

(Illustrations follow text)

1970 to 1980: The Havana Years

Carlos Alfonzo had a stellar career as a young artist emerging in the 1970s in Havana under the Castro government. He studied art, worked in a converted studio garage in his mother’s home, taught, read, wrote poetry, and became a recognized artist. The extent of his exhibition career, as noted in his biographies, is astounding.[2] He was a recipient of several important awards. His work was exhibited on a yearly basis, mostly in Havana but also throughout the island and abroad during this decade. Between 1970 and 1980, the artist had become a prominent artist among the ‘70s generation that the revolutionary government promoted.Carlos Alfonzo studied at the San Alejandro Academy of Fine Arts / Academia de Bellas Artes San Alejandro from 1969 to 1972, where he received his degree in painting, printing, and sculpture in 1973. During his years at San Alejandro, he taught art between 1971 and 1973. The following year, in 1974, he began to study art history at the School of Arts and Letters at the University of Havana, where he received a degree in 1977. Based on an account of the courses taken by a former student in the department, the curriculum covered a broad range of art history that included World History, the History of Art, Baroque Architecture, Aesthetics, African Art, Cuban Art, Oriental Art, and Art Theory.[3] For third and fourth year students, Monographic Courses offered included Modern Architecture, Pre-Columbian Art, and Twentieth Century Art.

After Alfonzo finished his formal studies at the University of Havana, he was assigned by the National Council of Culture (Consejo Nacional de Cultura) and, later, the Ministry of Culture (Ministerio de Cultura), to teach painting, sculpture, and drawing at cultural and vocational centers in the Havana area from 1973 to 1980.[4]

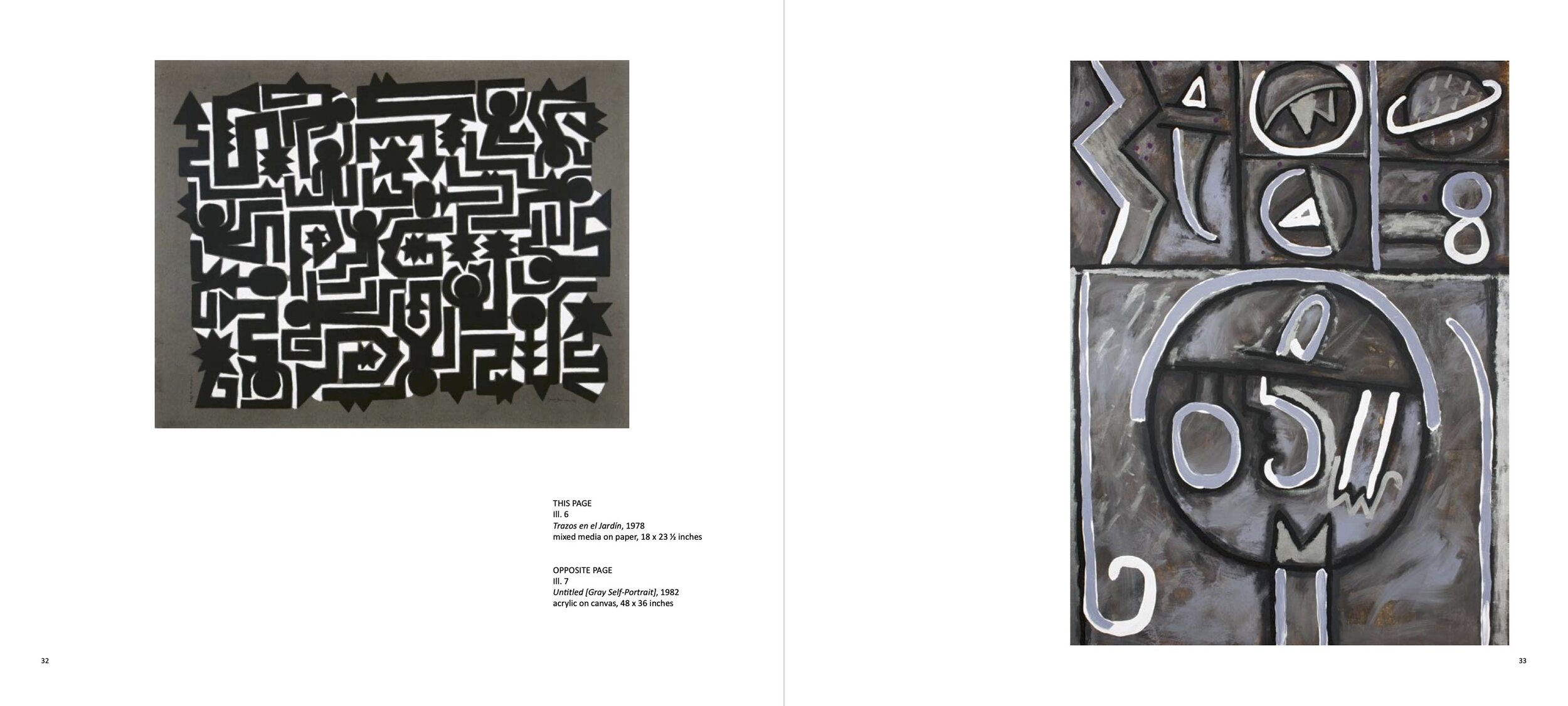

During that decade, Alfonzo developed a diverse stylistic language. His practice included small-scale works on paper or cardboard, with ink or mixed media, ceramics, and some sculptural pieces. He signed his work either C.J. or Carlos José. Witnessing Perpetuity includes Untitled I, II, III, and IV and Yo nunca te tuve bajo un árbol, from 1976, and Tribal Series I, II, and III, from 1979.

Untitled I, II, III, and IV are reductive drawings that feature flat, graphic-like images of a girl, a tree, an arrow, three flowers, and a curving serpent-like line in five basic colors: black, blue, yellow, red, and green. (Fig. 4, 1, 3, 2) In their extreme simplicity, Alfonzo may have been channeling Paul Klee, whom he admired.[5] We don’t know if this series was a one-off. We know more, however, about an extensive series of forty-two works on paper that were produced over a one-year period for the exhibition Como una vieja estampa. That exhibition was presented by the Consejo Nacional de Cultura at the Galería Amelia Peláez in June 1976.

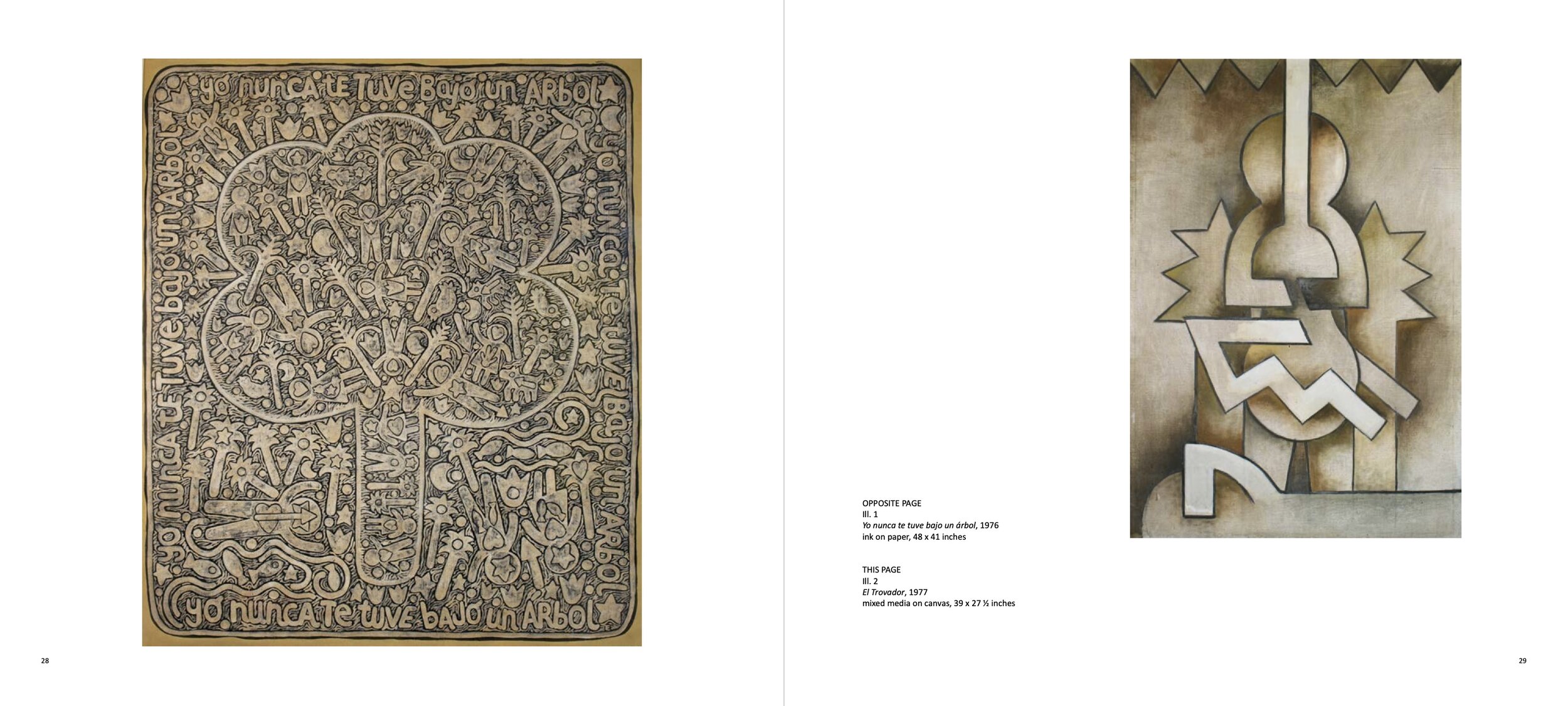

The exhibition title, Como una vieja estampa, comes from a line in the first verse of a poem by Nicolás Guillén, and is the same title as one of the forty-two drawings in the series. The artist’s writing at the top and bottom of the drawing comes from three lines in the second verse of the poem, “Tu recuerdo / Your Memory.”[6] The titles of the other forty-one drawings were taken from verses by poets such as Pablo Neruda and Violeta Parra or by Silvio Rodríguez and Pablito Milanés, two of the greatest musicians of that time who led the nueva trova musical movement, or by Alfonzo himself.[7] Yo nunca te tuve bajo un árbol (Ill. 1) is listed as checklist number 33 in the original brochure. The drawing on paper typifies the dense, overall compositions that minutely depict the flat, highly stylized graphic figures of trees, male and female figures, three-quarter moons, flowers, fish, stars, arrows, and curvilinear serpent-like lines. The verse “yo nunca te tuve bajo un árbol” is written on the four sides of the paper in the same style as the figural designs. Thus, writing becomes imagery.

In the two-page text for that exhibition, the essayist José Eladio defined Alfonzo as an artist, poet, and painter. Eladio praised Alfonzo for capturing in a visual language: “Our love of the nation. . .” (Nuestra patria es de gran amor . . .). In the brochure’s interview, “Conversa con usted Carlos José,” Alfonzo spoke about his work in poetic rather than in ideological, nationalistic political terms. The artist expressed the importance of “love” as the principal subject of the work in his first solo show. He said that if he is going to talk about his country, he would have to talk about love in its varied facets, [because] it is a broad subject (tema amplio), a universal one (universal), [and] a daily one (de a diario). Alfonzo chose to represent the concept of love through a symbolic language expressive of “the heart” (en mi trabajo aparece el corazón).[8]

We now know that Alfonzo continued to poetically title his works when he exhibited in the Pequeño Salón of 1977 in Experimentos de Carlos José Alfonzo. The artist showed a total of eleven small-scale works, three in mixed media on paper and eight in terracotta. He continued titling his works in a poetic vein that was captured in the exhibition’s small brochure, in the brief words written by Sergio López García, titled “Poesía, amor y optimismo” (Poetry, love, and optimism). Alfonzo’s titles referred to the time of day: El alba, La tarde, La noche (The Dawn, The Afternoon, The Night); others to places, En la playa (On the Beach), Trazos en la arena (Outlines in the Sand); another suggests the feelings of poets, El poeta se arrepiente (The Poet Regrets), and a further references lovers, La pareja (The Couple).[9] These titles, devoid of political content, seem to suggest the deep-seated sense of romantic feelings, even autobiographical states of mind, central to the artist’s work in Miami post-1980.

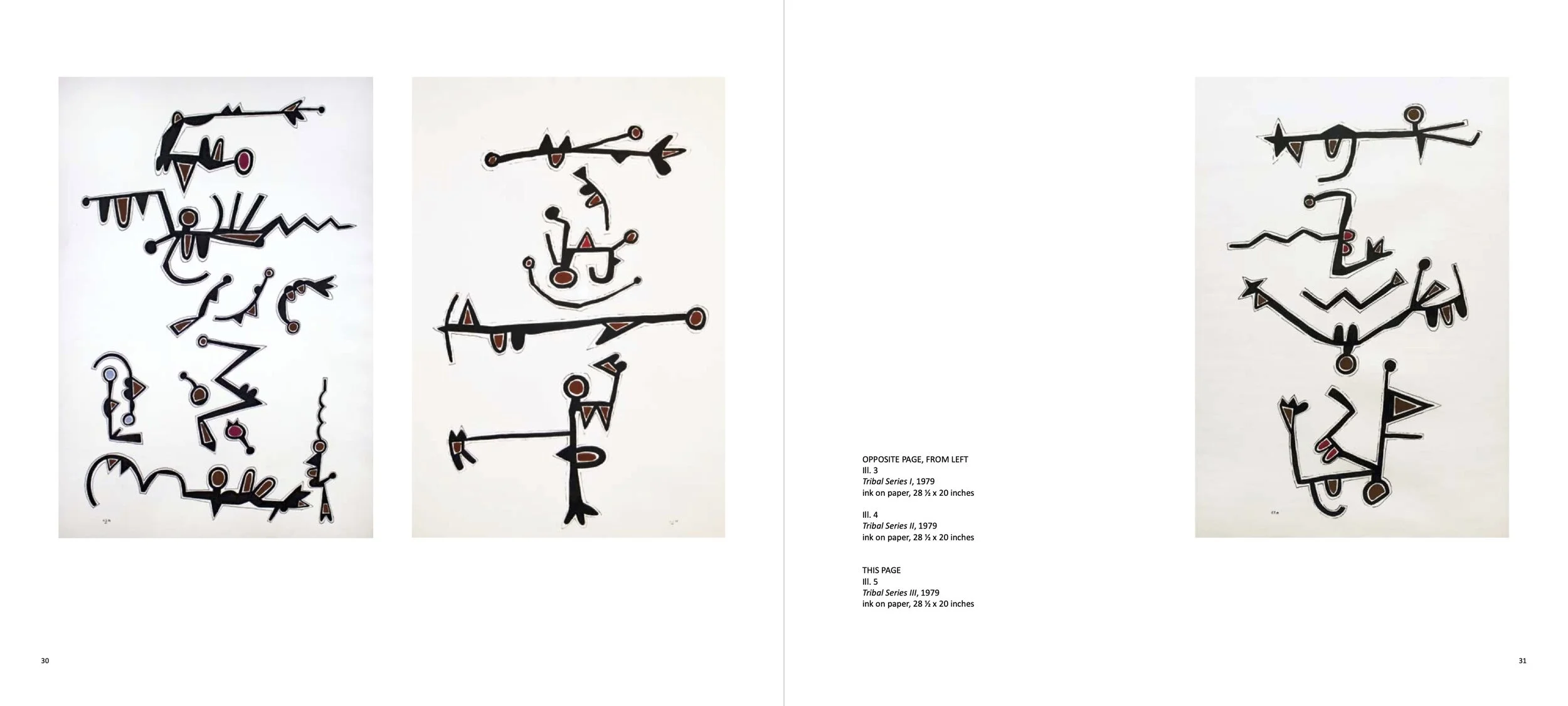

Tribal Series I, II, and III from 1979 (Ill. 3, 4, 5) recall certain works by Wifredo Lam for their bold, disembodied, energized configurations.[10] Exercising his highly developed graphic skills, Alfonzo created, in small scale, silhouettes of anthropomorphic figures defined in black and white against the light background of the paper, seemingly arrested in time and space.

Alfonzo had three solo exhibitions prior to the Tribal Series. These included: Como una vieja estampa and Experimentos de Carlos José Alfonzo, presented at the National Museum (1977), both noted above; and La tarde y sus dibujos (1978), a traveling exhibition in Cuba. These three, in addition to many group shows during those three years, established Alfonzo’s reputation throughout the ‘70s.

From a historical perspective, several interesting events occurred in 1979 worth relating. In that year, 100,000 émigres from the U.S. were allowed to visit their relatives in Cuba. Their stories of life in the U.S. left a great impression on many, notably because the economic conditions of Cuban-Americans were starkly better than those of their Cuban relatives on the island, who had been mostly unaware of the differences they now heard.[11] No doubt Alfonzo, who also had contacts with friends and family in Miami, was aware of new opportunities that were ninety miles off the coast of Cuba.

According to Victor Triay’s research, the influx of so many émigrés stirred the desires of many Cuban islanders to leave. Whatever the nature of the political stirrings that year, a group of close-knit artists—José Bedia, José Manuel Fors, Flavio Garciandía, Gustavo Pérez Monsón, Leandro Soto, Tomás Sánchez, Juan Francisco Elso, Rubén Torres Llorca, Rogelio López Marín (Gory), Ricardo Rodríguez Brey, Israel León, Emilio Rodríguez, and Carlos Alfonzo—decided to hold a private, one-day exhibition in José Manuel Fors’ home. (Fig. 5) Pintura fresca was inaugurated on October 19, 1979 and, by choice, closed that same evening after the opening. Alfonzo showed two works on paper, one of them stylistically similar to the Tribal Series (1979), in which he worked at the intersections of image and writing.[12] Following the October exhibition, Leandro Soto, one of the artists in the Pintura fresca group, organized the same exhibition at Galería de Arte Cienfuegos on November 17.[13] (Fig. 6) Gory vaguely remembers that Alfonzo did sculptural chairs in openwork wood, with painted figures, such as those made in cut paper. When the exhibition ended, the work went back to Fors’ home where most of it remained for at least a year.[14]

Following the closing of Pintura fresca in Cienfuegos, each artist continued to work independently, still many of them frequently got together to figure out how they could exhibit again as a group. Approximately a year and a half later in January 1981, the group showed their work in the Centro de Arte Internacional La Habana. In a serendipitous moment during installation, one of the artists suggested the title, Volumen I, after the English rock group Led Zepellin’s first album, Volume I.[15] Volumen I has had a consequential history in Cuban art but Carlos Alfonzo, one of the group’s original members, did not take part in that exhibition because he had already left the country on the Mariel boatlift in April 1980.

We don’t know exactly how long Alfonzo had been dissatisfied with life in Havana. He apparently told Rubén Torres Llorca, who was also in Pintura fresca, that he felt sad because all his friends had left the island.[16] Many Cubans who continued to feel a new level of discontentment in 1980 participated in acts of disobedience, some of which included people who tried to escape by boat.[17] Clearly “revolutionary” life did not suit Alfonzo. He must have loathed the many levels of the government’s surveillance and censorship; he had to hide his homosexuality and religious practices; and he doubtless yearned to travel outside of the island.[18]

Sergio Cernuda, Luisa Lignarolo, Julia P. Herzberg at opening of exhibition Witnessing Perpetuity, Feb. 2020.

April 1980 – July 1981: The Mariel Boatlift [19]

On April 1, 1980, six Cubans commandeered a bus that crashed through the gates of the Peruvian Embassy, causing the beginning of a nightmare experience for many.19 Alfonzo likely entered the embassy between April 4, after the Cuban guards no longer protected the entrance, and April 6, when there was a stampede of thousands into the embassy.[20] Whatever the exact day, Alfonzo suffered the same conditions as the multitudes who did not receive enough food or water or sanitation from within or aid from outside organizations. The artist was confronted with the chants of thousands of marchers who accused the asylum seekers of being “worms.” Conditions became so intolerable for the artist that he had a breakdown. He was fetched from the Peruvian Embassy by Dr. Jorge López Valdés and taken to a psychiatric clinic.[21] The doctor was able to secure a safe conduct visa for him to leave the country without his having to return to the embassy.[22]

Once home, life continued to be rather intolerable. Neighborhood Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDR) threw eggs at his house and chanted offensive messages. At some point in April, the artist boarded a boat in the Mariel harbor and left for Florida. When he arrived in Key West, he was sent to be processed in Fort Chaffee in Arkansas, which was opened on May 8.[23] There were 19,000 people resettled there in a camp that had significant problems. According to Triay: “Although the refugees were fed and provided for materially, the prison camp atmosphere, the disorder, frustration, lack of security, and bureaucratic chaos brought tensions to a boiling point. Riots broke out in June.”[24] Finally Alfonzo arrived in Miami on July 2.

Upon reflection, the physical and emotional damage the artist suffered during April in Cuba affected him to the extent that all the difficulties he experienced during the two months in the internment camp in Fort Chaffee were secondary to the personal hardships of getting asylum.[25]

July 1980 to July 1983: Miami

Alfonzo’s first few years in Miami were very difficult. While he supported himself with a variety of odd jobs, he had to overcome the memories of the terrifying experiences suffered while trying to leave Cuba. He thought of himself as “a total wreck [who] felt weak and emotionally undermined for a long time.”[26] After connecting briefly with family, he reunited with a former boyfriend from Cuba.[27]

Alfonzo recalled that it took a couple of years to get back to painting full time.[28] So far, only Figures from 1980 has been recorded in the writings on the artist. In 1981, he produced a number of works including Song to My Son and Good-Bye (Adios), both of which speak to loss. The first was an homage to his son who was only six when the artist left Cuba;[29] and the second, a farewell to his country.[30] The works are stylistically different: one is a simplified graphic design; the other, an overall drawing. However, they both feature the head and the three- fingered hands, motifs that are reformulated throughout the artist’s career. As tentative as the artist’s practice was at that time, he received his first invitation to participate in Art 10, a small, local group exhibition at the Koubek Center, a community space overseen by the University of Miami. His work was also included in a traveling exhibition Joan Miró 20th International Drawing Competition, Fundació Joan Miró in Barcelona.

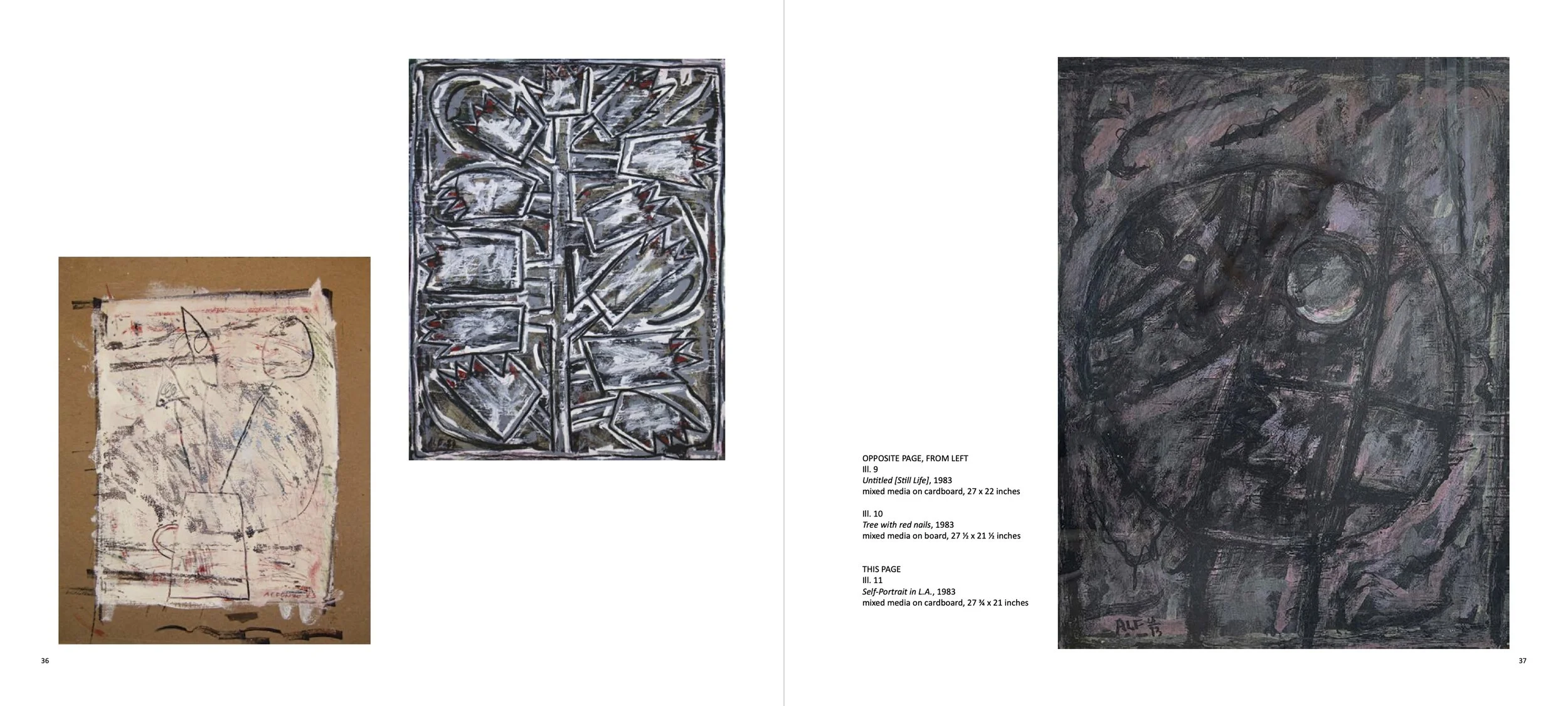

Alfonzo did more work in 1982 than he had the previous year. Several works, including an untitled painting descriptively noted as Grey Self-Portrait, have never been exhibited. (Ill. 7) It was one of several gifts to a dear friend, who has lovingly kept them through the years. The artist began to work in a slightly larger scale than he had in Cuba while retaining the graphic marks and using a limited color palette, as noted in earlier work. The motif of the head predominates; the composition divides into a box-like or grid structure that features pictographic markings, recalling Adolf Gottlieb’s mid-1940s works. Llamada a La Habana (Call to Havana), (signed ALF) expresses the need to communicate, probably with someone dear on the island.[31] The grin or corncob smile and the extended hands make their appearance in the grid structure. All the gloves for tomorrow will die... as us (signed ALF 11/82) looks back to some extent on Tribal Series (1979). A primitivizing, graphic language is deployed, as is the surrealist commingling. Arms morph into strange hooded figures, three-finger hands abound, and the knife makes its appearance. Gottlieb comes to mind regarding the structural composition. What distinguishes this particular work is the artist’s hand-written verse on the top, “all the gloves for tomorrow will die,” and, on the bottom right, under the image of an arm, the words, “as us,” a somewhat ominous message and one that presages others to come.

In 1982, Alfonzo was invited to participate in 10 Out of Cuba: A Selection of Cuban Painters. (Fig. 7) The exhibition was organized and curated by Inverna Lockpez, at the INTAR GALLERY of LATIN AMERICAN ART in New York, a premier nonprofit gallery that focused on Latin American artists. Lockpez was the first to organize an exhibition of artists, known as Marielitos, who had come to the United States on the Mariel boatlift in 1980.[32]

While the artist was in New York, he stayed with a friend and visited the Museum of Modern Art, the Solomon R. Guggenheim, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[33]

He was overwhelmed by seeing such a great range of artistic expressions that he admitted took him a good while to absorb. He confessed, as well, that after seeing the exhibitions in those museums, he felt that “I had never really known how to paint.”[34]

Two untitled works from 1983 feature the artist experimenting with the subject and form of a still life. Untitled [Still Life] is the more traditionally rendered in terms of its motifs—a pitcher with three objects against loose brush strokes on a light background— drawn as if it were a picture on the wall. (Ill. 9) The second, untitled drawing on paper [Platero y yo], of a similar size, features graphically rendered objects in and around a pitcher. (Fig. 8) Its imagery is similar to the larger painting Platero. The title comes from a beloved children’s book about a donkey. The book, a classic for many generations of readers, was written in 1914 in lyrical verse by Juan Ramón Jiménez, the Spanish writer who won the Nobel Prize in literature in 1956. Alfonzo’s choice of title forefronts his childhood memories and his unspoken love of literature, a touchstone in his visual work.

Alfonzo, together with César Bermúdez, was in Cuban Fantasies at the Kouros Gallery in New York in the spring of 1983. Giulio Blanc selected Alfonzo’s Song to My Son (1981) for the cover of the small brochure. Around the same time, the artist also participated in Faces and Masks at Galeria Ocho at the Miami-Dade Community Center. César Trasobares, the founding director and curator, had met Alfonzo that year and became one of the key people who recognized his talent and introduced him to the local arts community.

July 1983 to April 1984: Los Angeles

In the summer of 1983, Alfonzo took off for Los Angeles, needing a total break from the difficulties of readjusting to life in Miami during a period still haunted by his Mariel exodus. Since he had also lost his job and began to collect unemployment, and had split with a long-time partner, the time seemed right. He had a friend in Los Angeles, with whom he stayed until about April 1984, when he returned to Miami. By his own account, he did not have an active social or cultural life in L.A. Apparently, he met few people, stayed away from art galleries, and visited the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art only once. He had saved some money from Miami, received a CINTAS Foundation Fellowship in the Visual Arts, and used the time to think about himself and his work.[35] He did a few paintings that recall familiar motifs, graphic markings, and compositional formats as they forged new formal and thematic directions.

The motifs of the three-fingered hands in the rectangular composition, Trees with red nails, signed ALF LA/83, are reconfigured along a vertical element that could be, were it drawn realistically, the stem of a flower. (Ill. 10) The artist did several other works, such as Last Tears, Red Downtown Judy, and Untitled [Planes], that are all signed ALF LA/83.

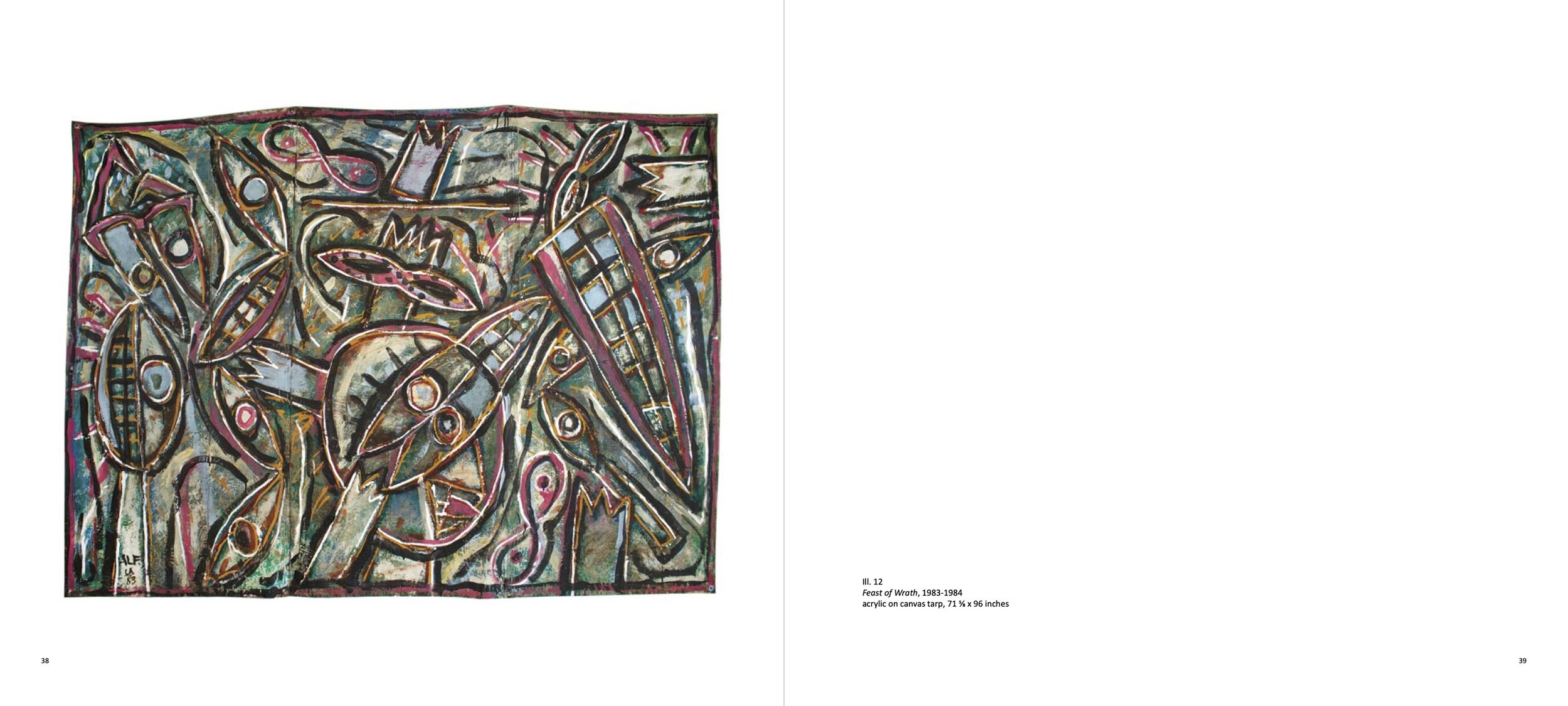

Each of these works, painted on board or paper in a relatively small scale, is colorful, painterly, and more complicated in terms of the spatial organization and the overlay of forms.[36] Although these works are all highly regarded today, Alfonzo prioritized his breakthrough moment. As he told it, he bought some tarp because he couldn’t afford canvas and one day began a new work that he felt turned out to be wonderful. He used bright colors, such as corals, blues, yellows, and greens, and he found that his brushstrokes were free and expressionistic. “It was my first important painting . . . Painting that picture [Feast of Wrath, signed ALF LA/83] was a real joy for me, and it came easily.”[37] (Ill. 12) Feast of Wrath features interlocking and superimposed images of heads and necks, eyes, corncob mouths, half-masks, and jutting hands. Each motif, outlined in black, white, and ochre, seems to spring off the blue-green background. Alfonzo contained the movement within the canvas by painting border-like lines around the perimeter.

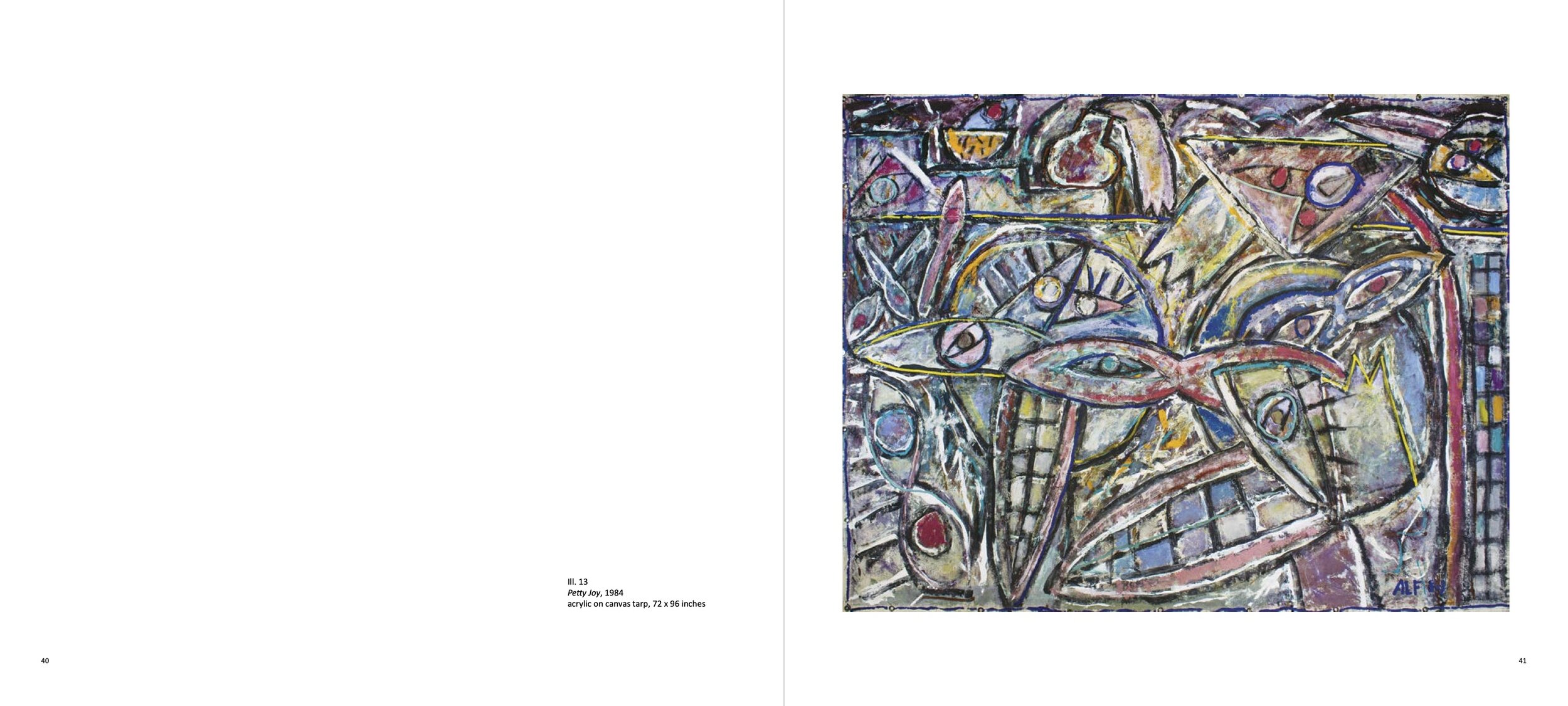

When the artist finished Feast of Wrath, he knew he had reached a turning point in his career and, as a result, was ready to return home to Miami. From the spring of his return, he continued to develop the new-found expressive freedom he had experienced in Los Angeles. Witnessing Perpetuity, at LnS Gallery, features Petty Joy, (Ill. 13), and Largo One (Fig. 9). Petty Joy is a painting of an interior, as are many, according to the artist.[38] In this bold, colorful, energized, ultra-crowded space, the motifs of the eyes, spoons, carnival masks, corncob smiles, a shelf and its objects, and a lamp with a triangular shade and its light bulb clash. Alfonzo, it seems, was riffing on interior scenes painted by the Cuban modernist artist René Portocarrero.[39] Petty Joy was one of six paintings selected for the now-historic exhibition, Hispanic Art in the United States: Thirty Contemporary Painters & Sculptures, one of the first nation-wide traveling exhibitions that changed the discourse on contemporary Hispanic artists living and working in this country.[40]

Largo One has an interesting history. It was one of four equal-sized, horizontal works (Largo Two, Largo Three, and Largo Four) intended to be hung side by side, in Carlos Alfonzo: Drama, organized by César Trasobares at Galeria Ocho, in Miami-Dade Community College in October 1984.

Largo One is composed of heavily outlined eyes, circles, infinity signs, and daggers—all seemingly conversing with one another. The painting Drama has recognizable objects: a head and neck, a pair of eyeglasses, a comb, carnival masks, an infinity sign with eyes, three-fingered hands, a dagger and knife— all of which appear pulsating within the artist’s largest canvas to date. The “drama” seems to be the collision of images. Peter Menéndez, another close friend and unofficial artistic advisor of the artist, designed a beautiful handout featuring the artist’s drawing.

As it turned out, 1984 was the beginning of an auspicious period in that decade. Alfonzo became better known locally through the exhibition Young Collectors of Latin American Art, at the Metropolitan Museum and Art Center in Coral Gables.[41] The artist received a Visual Artists Fellowship in Painting from the National Endowment for the Arts. This award undoubtedly called attention to the curators (John Beardsley and Jane Livingston) who were considering their selections for Hispanic Art in the United States: Thirty Contemporary Painters & Sculptors.

1985 – The National Endowment for the Arts: Fellowship Artists, Florida 1983-84

This award brought Alfonzo national recognition in addition to increased local attention. The exhibition for the National Endowment Fellows was held at the Fine Arts Gallery at Florida State University in Tallahassee (February 8 – March 3). New Works: Carlos Alfonzo and Eugenio Espinosa was organized at INTAR LATIN AMERICAN GALLERY. (Fig. 10) Florida Figures: The Human Figure by Contemporary Florida Artists at the Frances Wolfson Art Gallery, Miami-Dade Community College (Sept. 6 – 30, 1985), was the first of several exhibitions curated by Sheldon M. Lurie, an important curator in the Miami art scene. Carlos Alfonzo: New Paintings at McMurtrey Gallery in Houston was his first solo show in a commercial art gallery (April 22 – May 27).

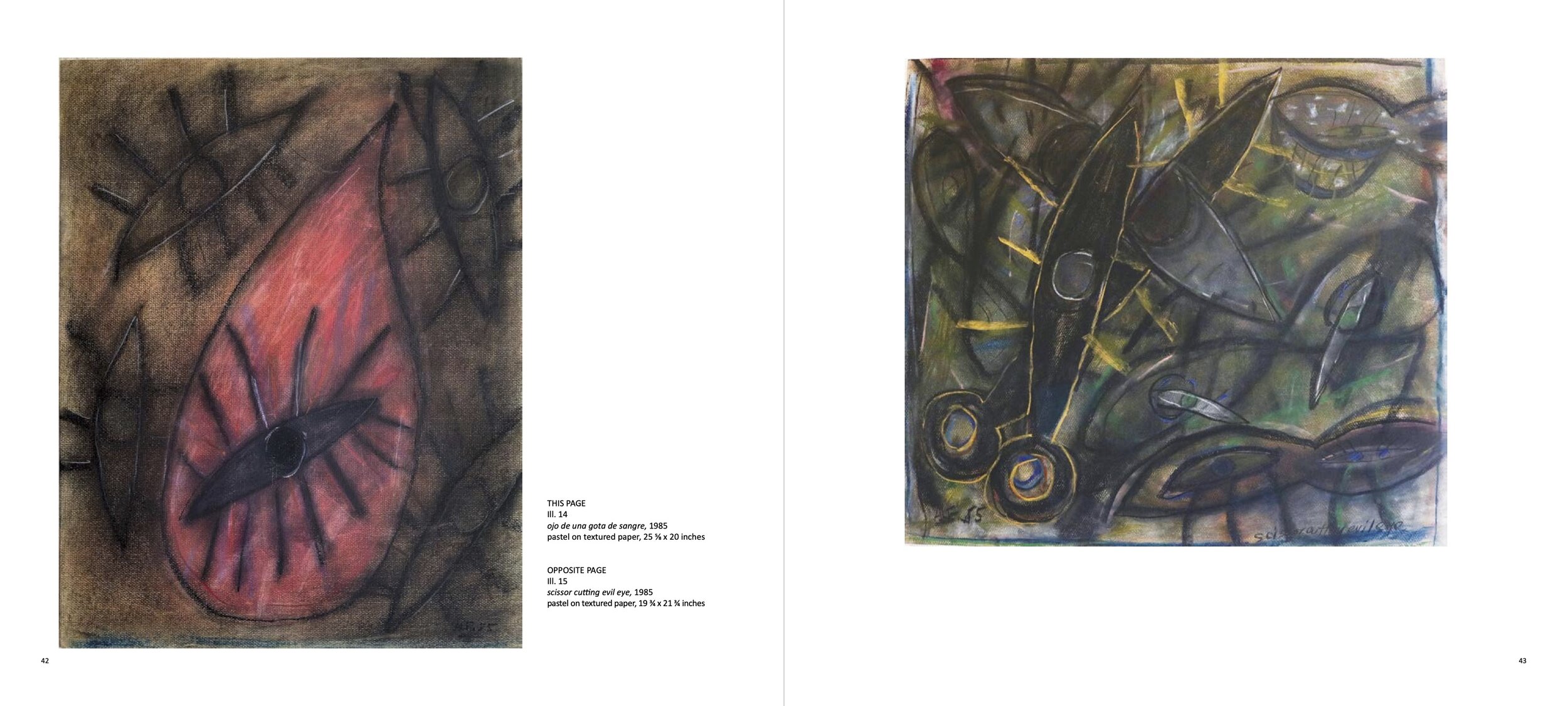

The exhibition at LnS Gallery has two very beautiful pastels on textured paper. Ojo de una gota de sangre (red tear drop) is titled in lower case on the back of the paper. (Ill. 14) The image of a drop of blood occupies center space; inside that red drop is the characteristic image of the Alfonzian “eye.” Small in scale, it feels intimate. Surrounding the red drop are four eyes. However you interpret this imagery, keep in mind that the eye is both a noun (organ for seeing) and verb (look or watch closely). Scissor cutting evil eye is also titled in lower case in the lower left. (Ill. 15) The overlaid images of the masks with the two eyes peering in different directions, drawn in pastels of deep rich colors highlighted by yellow marks, is as overwhelmingly beautiful as it is ominous—because the scissors intervened to ward off evil!

Trail writ large embodies a network of eyes (perhaps as many as seven), along with knives, drops of blood, a teardrop, a phallus, and the disembodied parts of the human figure.[42] (Ill. 16) Alfonzo had his own subjective story, one that viewers will decipher. The artist has said that he was not interested in narrative or anecdote. Rather, his interests lie in expressing a poetic, mysterious quality even though there are [at times] specific themes he unwinds.[43]

1986 and 1987: Engagement with the secular and the religious

The work of these two years reveals the kind of passion that Alfonzo admirers feel when looking at his work. He engaged secular subjects and also religious ones that embody, in turn, Catholic and Santería references.[44] The artist’s mother was a devoted Catholic until the Revolution. Her son grew up knowing her beliefs. He credited her for having given him the “opportunity to meet with magic.” While he was in art school, his friends secretly initiated him into Santería, which for a time informed his artwork in the United States.[45]

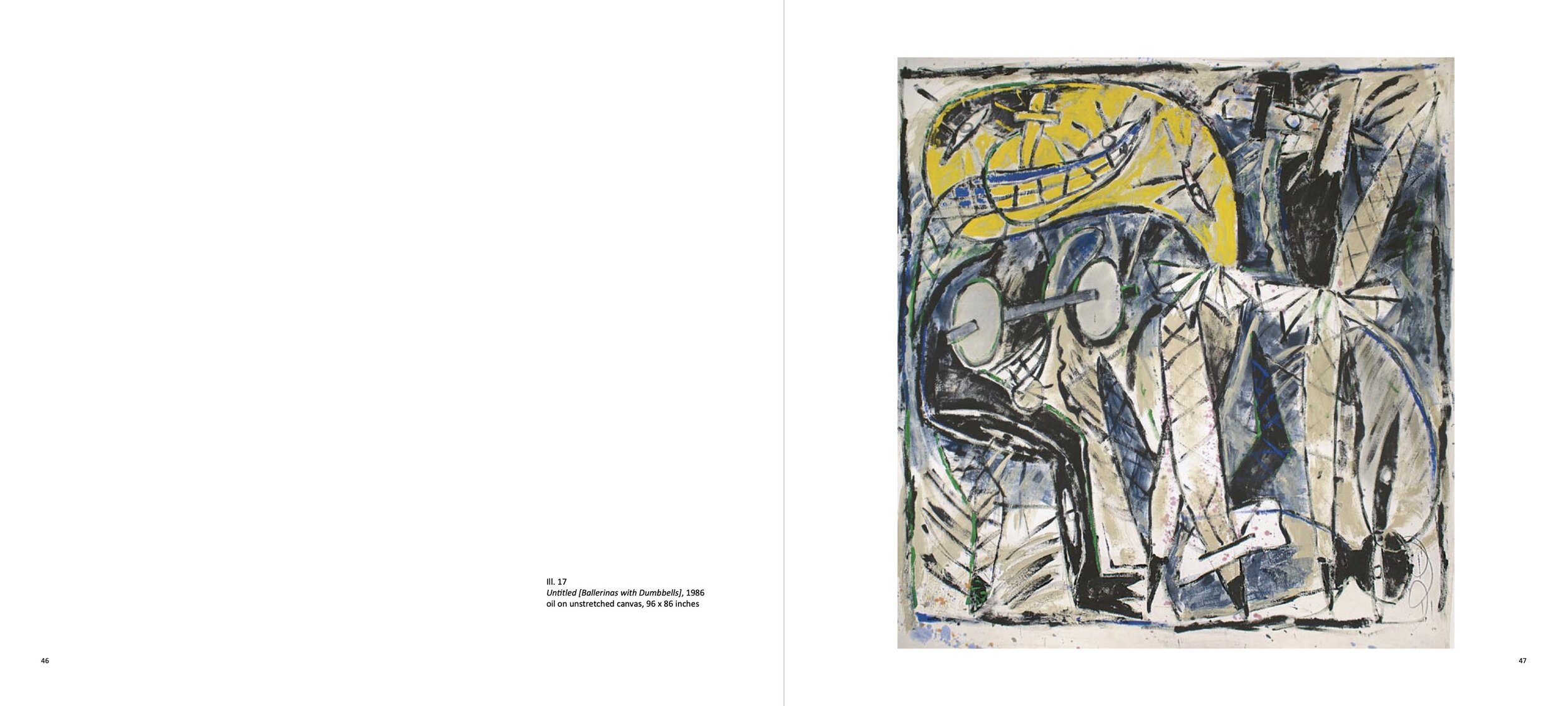

Untitled [Ballerinas with Dumbbells] conjoins several interests the artist had as well as several associations he made with the motifs of the legs of dancers on pointe, a figure lifting weights, and the phallus. (Ill. 17) There was a gym near Carlos’ house that he knew of—thus, the image of the dumbbells. He would have liked to collaborate with dancers—thus, the images of the ballerinas.[46] Another painting, Mad One Also Sleeps / El loco duerme también (1986), features similar motifs of a partially drawn ballerina, dumbbells, and an array of common objects seemingly tossed in every direction to confer a state of madness.[47 ]The artist always acknowledged the presence of evil and violence—thus, the daggers. He was not shy to express his sexuality as a gay man with the image of a phallus. Its frequent inclusion gave voice to his queerness, an aspect of his identity which he was proud to convey.

Sometime around mid-1986, Alfonzo went to Italy, where religious subjects informed his thinking and iconography.[48] He commented on the new ways he could transform the skull motif, after having seeing it in “old art and in the Capuchin Monastery in Rome.”[49] These varied shapes became primary ones in subsequent work. His references to Renaissance art, a style and period he loved, is often revealed through titles. After returning from Rome, he did Renaissance Man, a small ink on Stonehenge paper in three pieces, adopting the format of the triptych common to the religious art of that historical period. He also painted Memento Mori #1, which addresses the transience of life, an existential condition woven into the fabric of his later work. Aside from a solo exhibition in Houston, the artist participated in numerous group exhibitions in Coral Gables, Miami, New York, and Mexico City.[50]

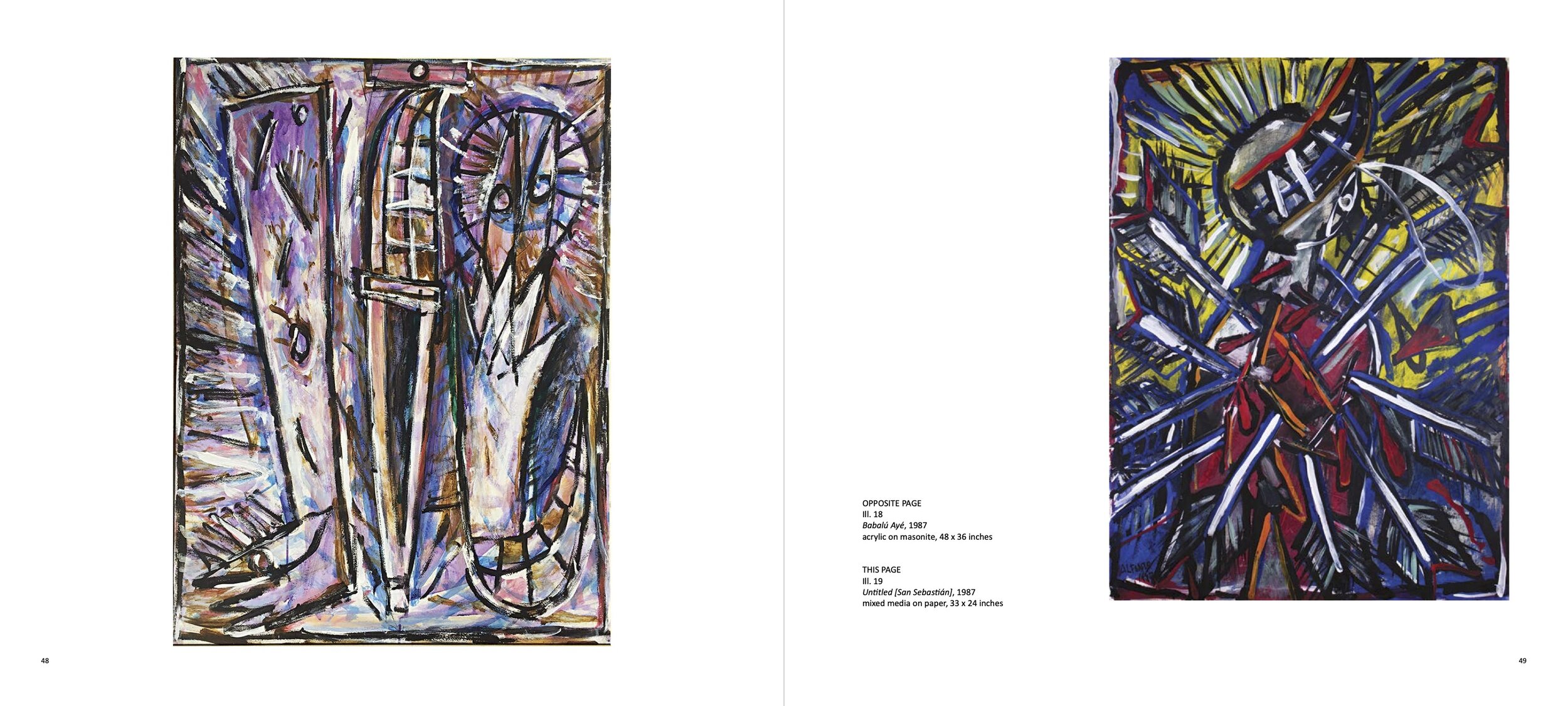

Alfonzo readily admitted the importance of his religious beliefs in art and life. As noted above, he secretively practiced Santería in Cuba. He did not depict Santería images until he came to the United States. Around 1983-84, the artist did some ten to fifteen different versions of Elegguá in a notebook, illustrating Lydia Cabrera’s El Monte, that he intended to publish in a book.[51] In 1987, he did a series of paintings and ceramics honoring some of the major deities, including Babalú Ayé (Ill. 18) and Yemayá. The paintings were intended as gifts for a local Santería center that was never constructed. Yemayá, believed to be the mother of the water, children, and all the orishas, is created in a palette of blues. Her head and neck occupy the center of the composition while large hands are depicted in multi-directions. Babalú Ayé, associated with Saint Lazarus, is considered the patron deity of those who are suffering from sickness or infirmity. Here, he is painted in blues, pinks, violets, and whites. Alfonzo applied gorgeous colors for three large images: a disembodied leg, a knife, and a metamorphosed head, hand, and spiral.

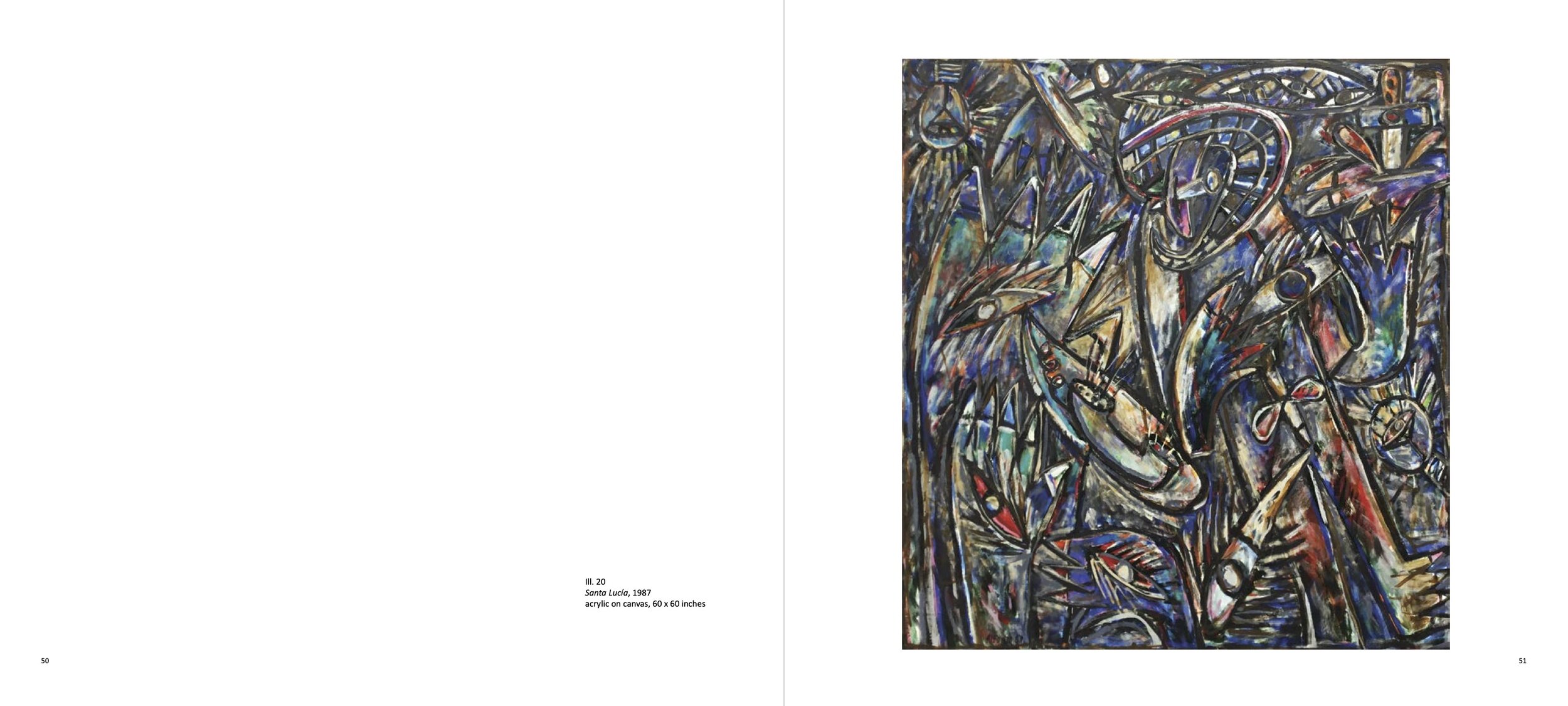

At some point after he was secretly initiated into Santería, he began reading about Catholic saints as well as the Old and New Testaments. Untitled [San Sebastián] (Ill. 19) and Santa Lucía (Ill. 20), both from 1987, are rendered as explosively in their graphic configurations, as are Babalú Ayé and Yemayá. Using his now well-defined post-cubist and post-surrealist idioms, his idiosyncratic vocabulary of thrusting hands, heads, arrows, blood drops, knives or nails in tongues, metamorphosed bodies, eyes, and usually a phallus define the compositions. And every now and then, an object appeared from the secular world, such as a telephone in Santa Lucía.[52] Saint Sebastian and Saint Lucy were early Christian martyrs. Saint Sebastian, the patron saint of athletes as well as of archers, is commonly depicted shot with arrows. (The saint has also been erotically rendered by many seventeenth and eighteenth-century artists.) In Alfonzo’s small painting, parts of the body, such as the head, neck, and outlines of the upper torso, are recognizable but his schematized torso is formed by arrows.[53] Santa Lucía, patron saint of the blind, is personified by a series of eyes depicted among many clashing motifs.

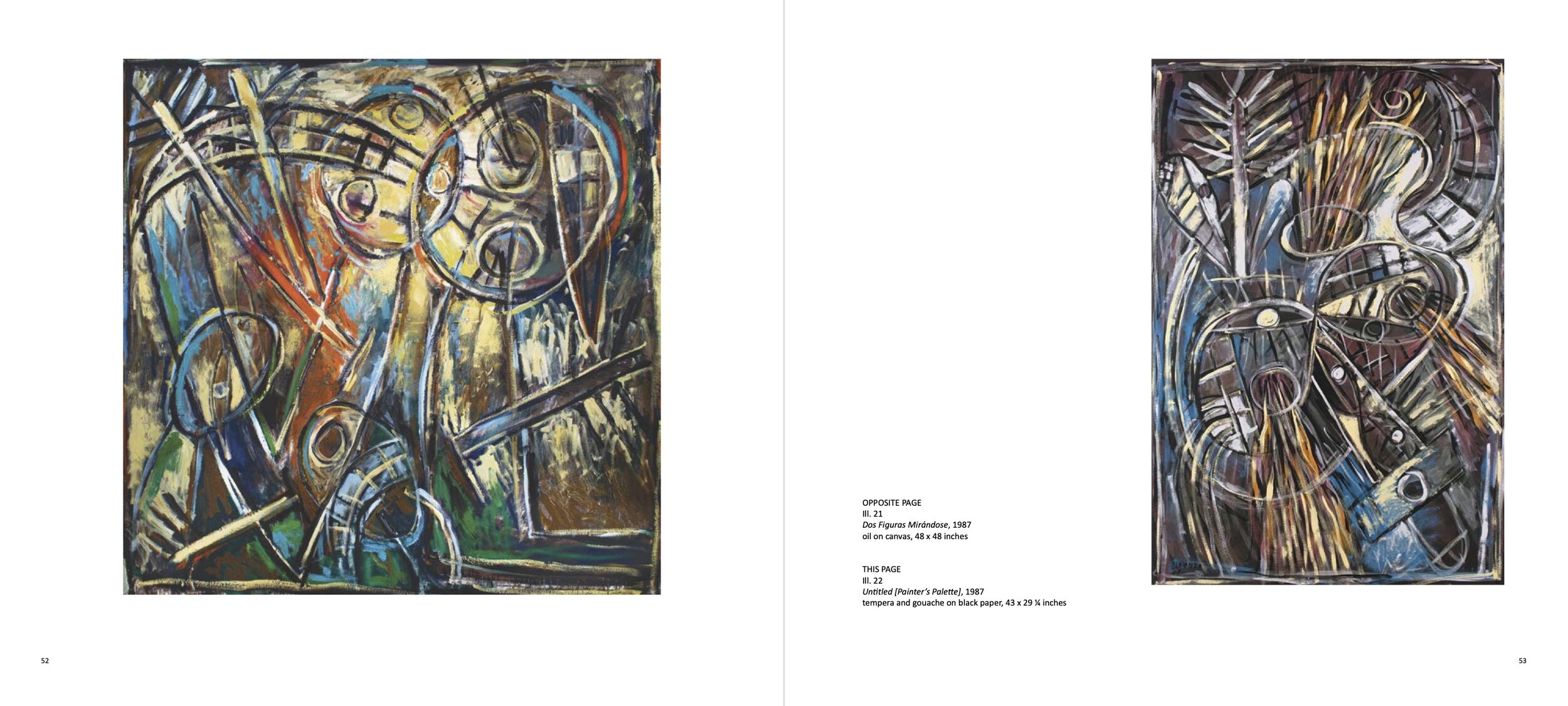

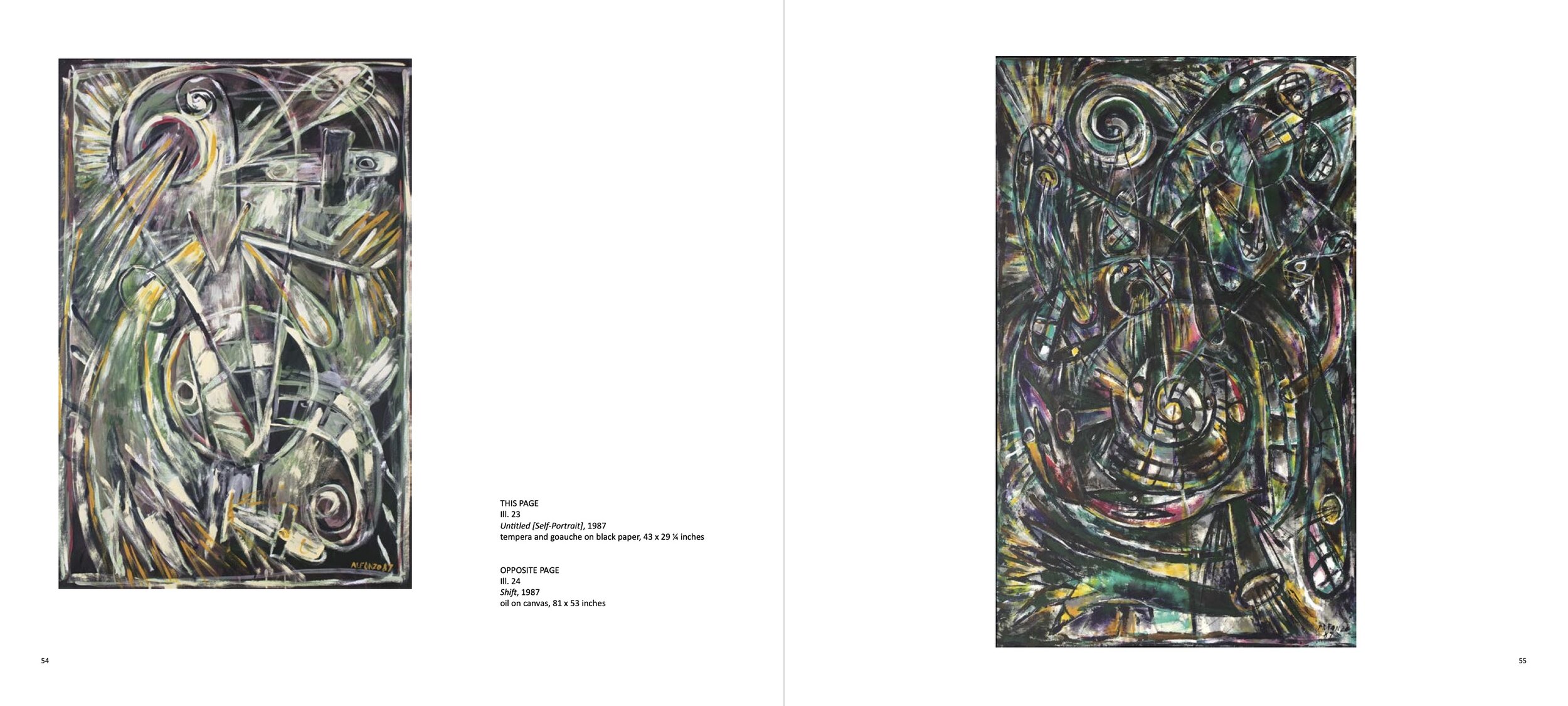

Untitled [Painter’s Palette] (Ill. 22) features the outline of a palette together with the flaming lines and familiar motifs. The self-portrait is intended as a universal signifier for the practice of painting. We are reminded of Pablo Picasso, Paul Cezanne, and Vincent Van Gogh, among many other artists, whose palettes were an extension of themselves as artists.[54] As in all of Alfonzo’s work, he destabilized traditional visual elements. The interconnected motifs in this painting, and in Untitled [Self Portrait] (Ill. 23), Dos Figuras Mirándose (Ill. 21), and Shift (Ill. 24) feature phalluses, infinity symbols cum heads, arrows, flaming lines, daggers, and eyes. These works are expressive of Alfonzo’s inner life. And each work is a tour de force, with a sense of dynamism that is barely contained within the painted lines around the borders of the work. Due to the dominant motif of the swirling phallus superimposed with penises and large tears drops (read semen or ejaculation), I cannot avoid thinking that the artist was focusing on the many men who were dying of AIDS.

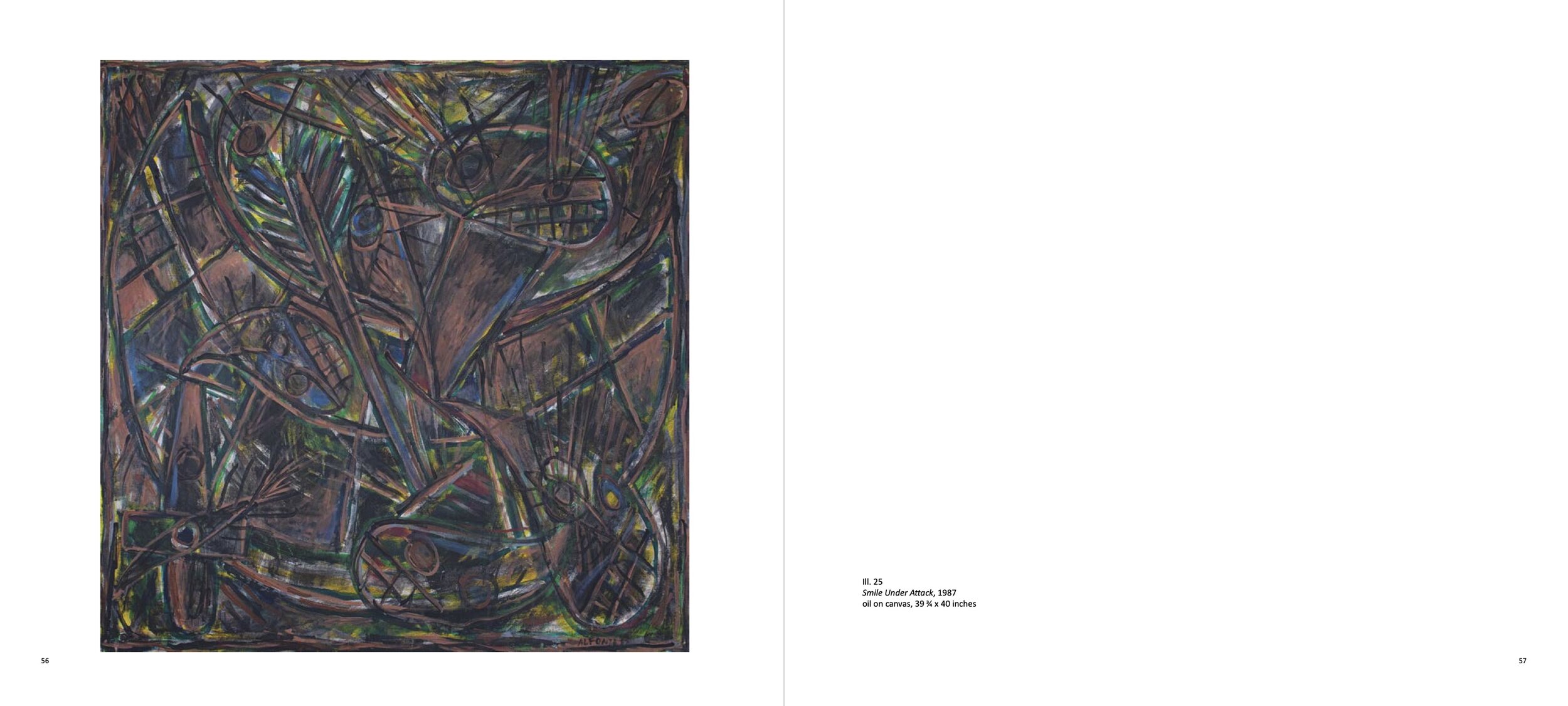

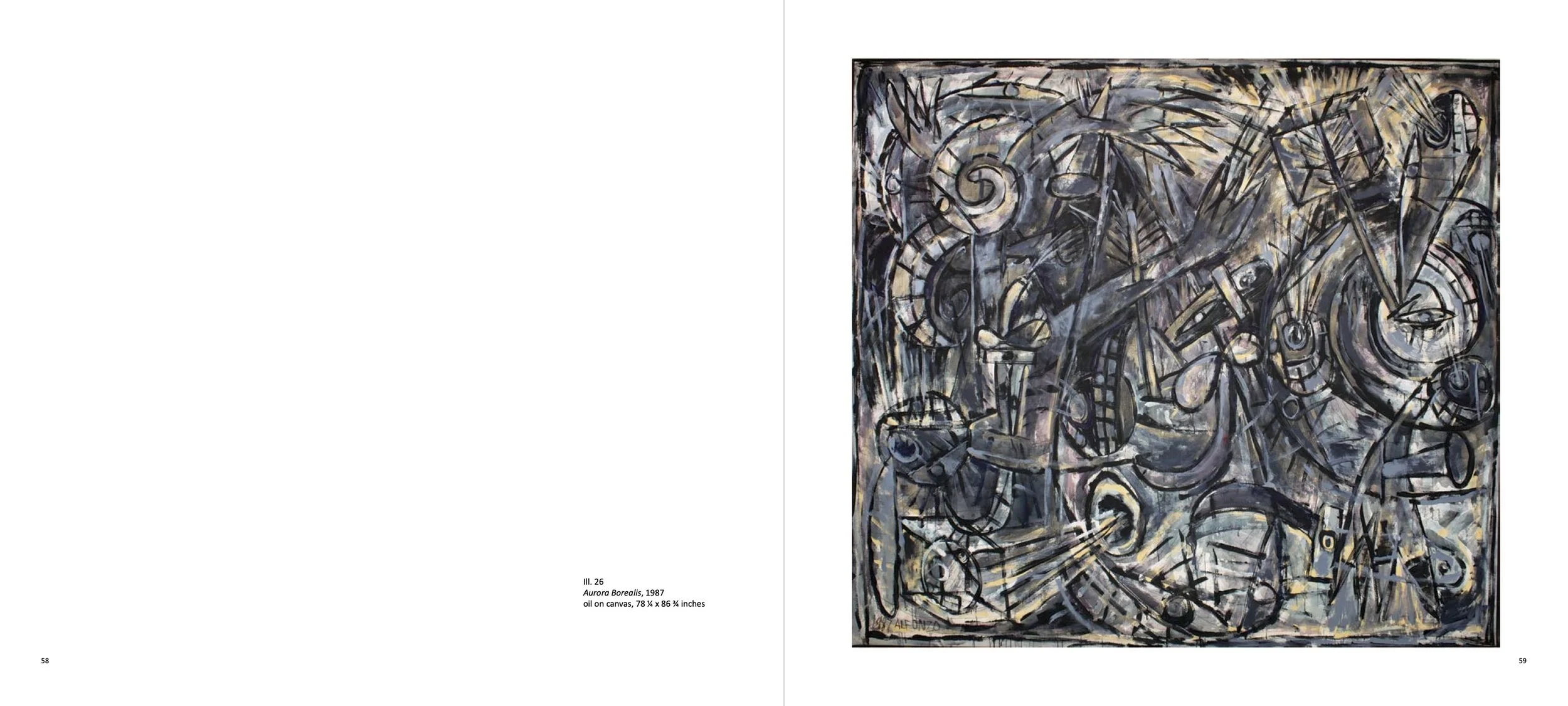

On November 6, 1987, Sheldon Lurie organized an art auction to benefit The Health Crisis Network. Art against AIDS was held at the Frances Wolfson Art Gallery, Miami-Dade Community College. It was the first event in South Florida generated by the visual arts community to assist the work of many anonymous individuals who constituted and supported the Health Crisis Network. Artists, art collectors, and art dealers donated artworks in a wide range of styles, media, and prices. Alfonzo donated Smile Under Attack (Ill. 25), which he titled in upper case letters on the back of the canvas together with the name of the exhibition. The artist also designed a t-shirt, to be sold to raise funds, which he was dressed in when he was buried in February 1991.[55] (Fig. 11-12) The title, Smile Under Attack, attests to the artist’s sense of humor and irony, two characteristics about which his friends have often commented. In terms of the painting’s iconography, the tangled imagery includes the outlines of a large head within which the world seems to be swirling! The conflation of arrows (read death), phalluses (read gender construction, sex), and shooting vertical colored lines (read energy) create an erotic topology gone awry! For the thousands who had already died and to those many more who would die, this work may be understood as an homage to those who suffered alienation, painful treatment, and death.[56]

1988 – Trip to New York: Drawings, Paintings, Ceramics, Sculptures

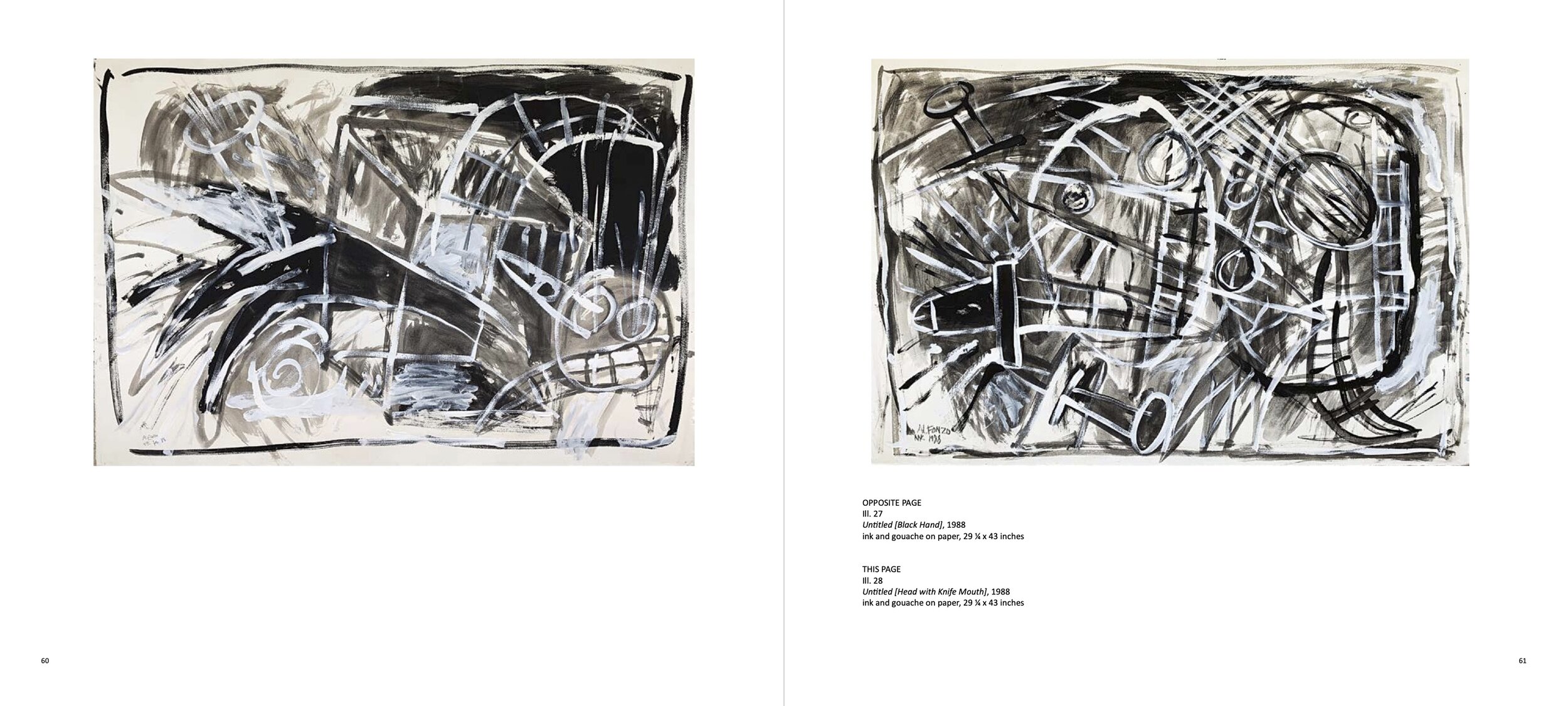

In February of 1988, Alfonzo visited New York to participate in Colliding: Myth, Fantasy, Nightmare at Artists Space. He stayed at a friend’s apartment and painted two works on paper as tributes, it would seem, to New York City. Identical in size and painted with ink, they have the artist’s hallmark motifs. Untitled [Black Hand] is distinguished from Untitled [Head with Knife Mouth] in that the one work features a large black hand crossing over the cube and phallus while the other has two heads, one of which is pierced by a knife. (Ill. 27 and Ill. 28) We recall that a tongue pierced by a knife or a hand pierced by a nail serves as an amulet to ward off evil. Alfonzo’s interest in creating metaphors for suffering or violence coursed through his work. Study No. 3 is a night scene, with its characteristically complex personal inventory of signs and symbols that includes the genitalia in the form of a figure eight.[57] (Fig. 13) This work was exhibited at the Barbara Greene Gallery, in New Work, in April.[58]

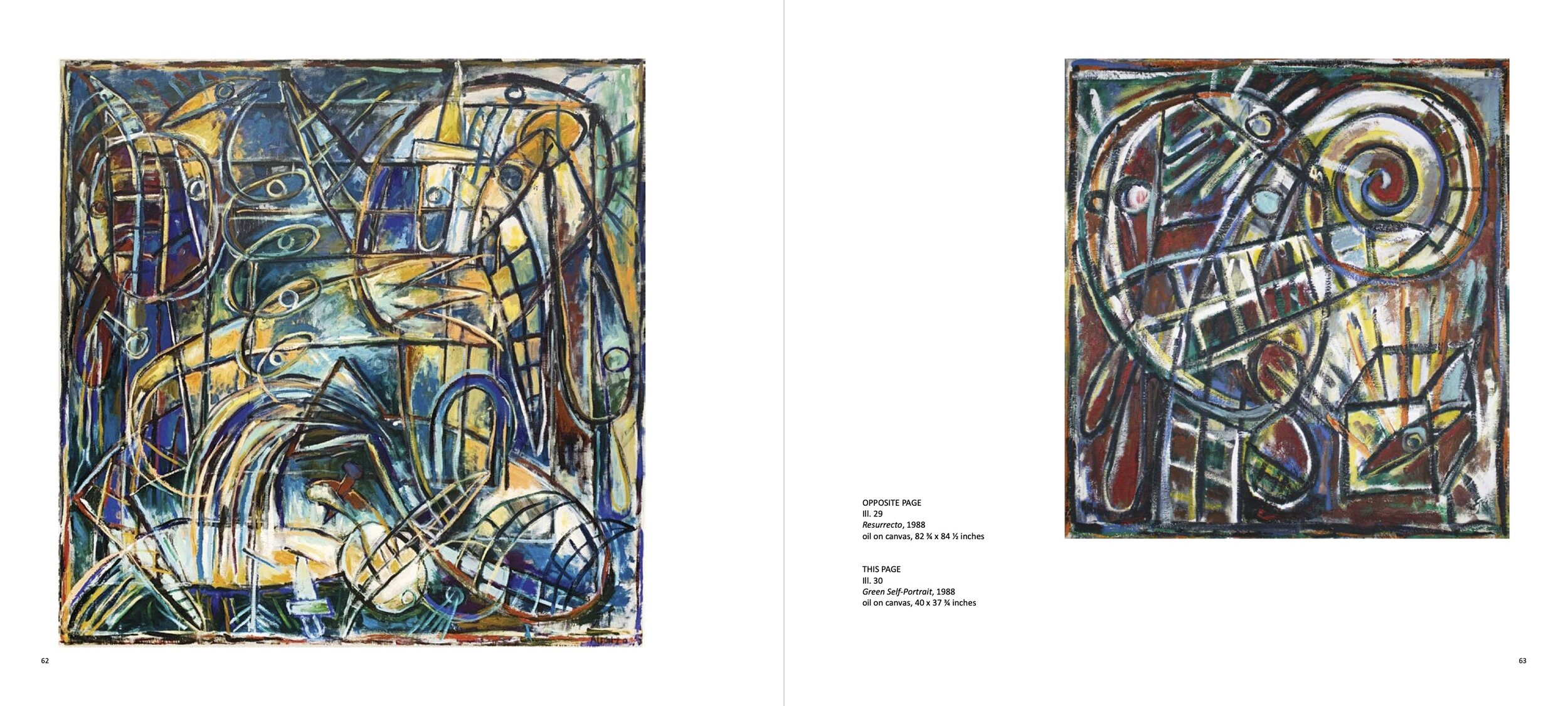

Resurrecto (which references resurrection, rising up) is an encyclopedic topography of Alfonzian symbols. (Ill. 29) Here, however, he included the images of two fish: one appearing to be swimming downward; the other to be jumping up. The artist often referred to water because it was part of his life and his country—from Cuba, to Key West, and, finally, to Miami. The artist has shared his view that he tries to communicate a sense of life’s mystery . . . as he struggles to understand his own place in what he senses is a great unknown.[59]

The self-portrait is a subject the artist embraced throughout his life. Art and the self are one and the same. In Green Self-Portrait, the large head occupies more than half of the pictorial space. (Ill. 30) It is overlaid with the large drop shapes (read semen, blood, tears), eyes, a cube with an eye and flaming lines symbolizing energy, and a ladder-like form that transforms into a spiraling penis. The vivid colors, brushy strokes, and black silhouetted forms call out: “Life, here I am!”

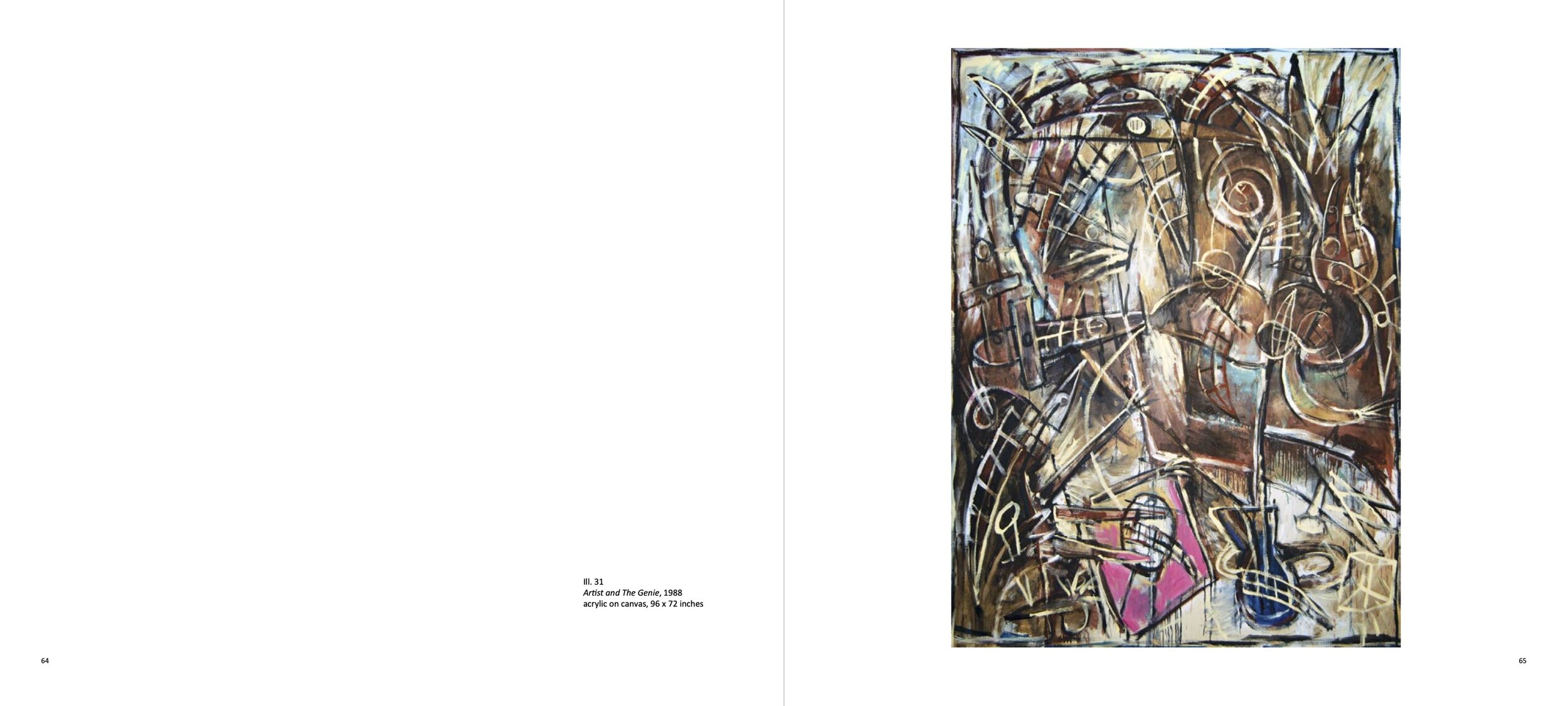

Artist and The Genie recognizes Alfonzo’s delight in expressing the magical aspects of life and imagination. (Ill. 31) A painting seems like a dance as well as a musical composition whereby the superimposed forms configure endless movement. As noted above, the artist credited his mother for having given him the “opportunity to meet with magic.” The genie here may just be jumping out of the pitcher in the lower right, hopefully to grant a good wish.

From the beginning of Alfonzo’s training and career, he worked across drawing, painting, ceramics, and sculpture. His work is undergirded, in different times, forms, and dimensions, by the lyrics of poets, the sounds of musicians, and the movements of dance. Let’s consider an untitled, glazed ceramic plate, one in a lineage of ceramic works from the artist’s early use of clay to his later use of underglazes and glazes.[60] (Fig. 14) The imagery in the plate reveals the free-flowing gestural application of brushwork and the overlaying of imagery, characteristic of his paintings. The hollow cubes stand for creation and eternity. The oversized tear, doubling for semen, arises from the cube with images of the corncob mouth, eye, dagger, and small nails. The overlapping imagery of flames, the figure eight, and the hand with a nail all create a clashing iconography.[61]

Alfonzo made small ceramic wares to use at home, to give as gifts to friends and to function as stand-alone sculptural forms (Fig. 15) as well as monumental public works.[62] His ceramic production followed the interests of many modernist artists, such as Wifredo Lam, Amelia Peláez, Pablo Picasso, and Henri Matisse, each of whom developed a significant body of ceramic sculpture that the artist admired.

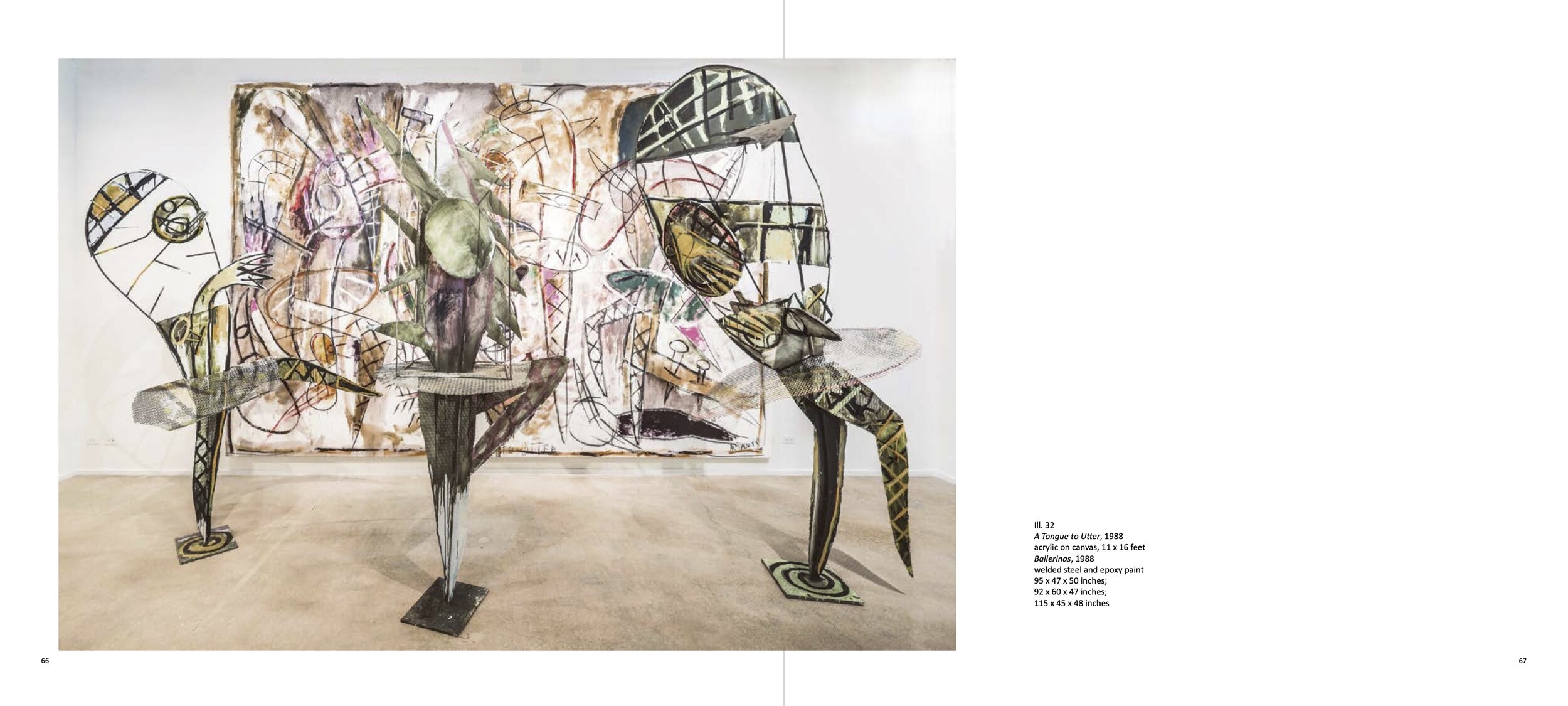

Alfonzo would have liked to have collaborated with choreographers and dancers, but that opportunity did not happen. Never one to avoid his artistic impulses, the artist created his own mise-en-scène, with the backdrop A Tongue to Utter and Ballerinas to accompany it. (Ill. 32) Ballerinas is an ensemble sculpture of three dancers on pointe, fabricated in steel, configured with a sense of expressive abandon. In syncopation with the forms in A Tongue to Utter, each dancer in Ballerinas morphs into a distinctive figure, similar to the inventively drawn figurations in his paintings.[63]

A Tongue to Utter begs the question: Would the tongue utter something positive or was to dispense a critical stab to Alicia Alonso’s allegiance to the Castroite regime.[64] The large painting, A Tongue to Utter, is populated by figures whose metamorphosed bodies seemed to dance on the surface of the canvas, as if in rhythm with the music that Alfonzo knew or listened to when he created them. Music was an art form that the artist preferred. He remarked that he would like to have been a musician; he made a promise that if he had time and things cleared up [in relation to his health] a bit in his life, he would “eventually study piano before I die.”[65] Alfonzo hoped that the mise-en-scène would have a public viewing, which it did, at the Lannan Museum in Lake Worth, Florida (January 28 – March 4, 1989).[66] At publication of this catalogue, A Tongue to Utter and Ballerinas are on long-term loan at the Lowe Art Museum in Miami. The ballerinas were probably the first sculptures that Alfonzo produced at Grapa, a small company in a warehouse district of NW Miami owned by Julio Grabiel and Ricardo Pau.

1989: Sculptures and Habitual

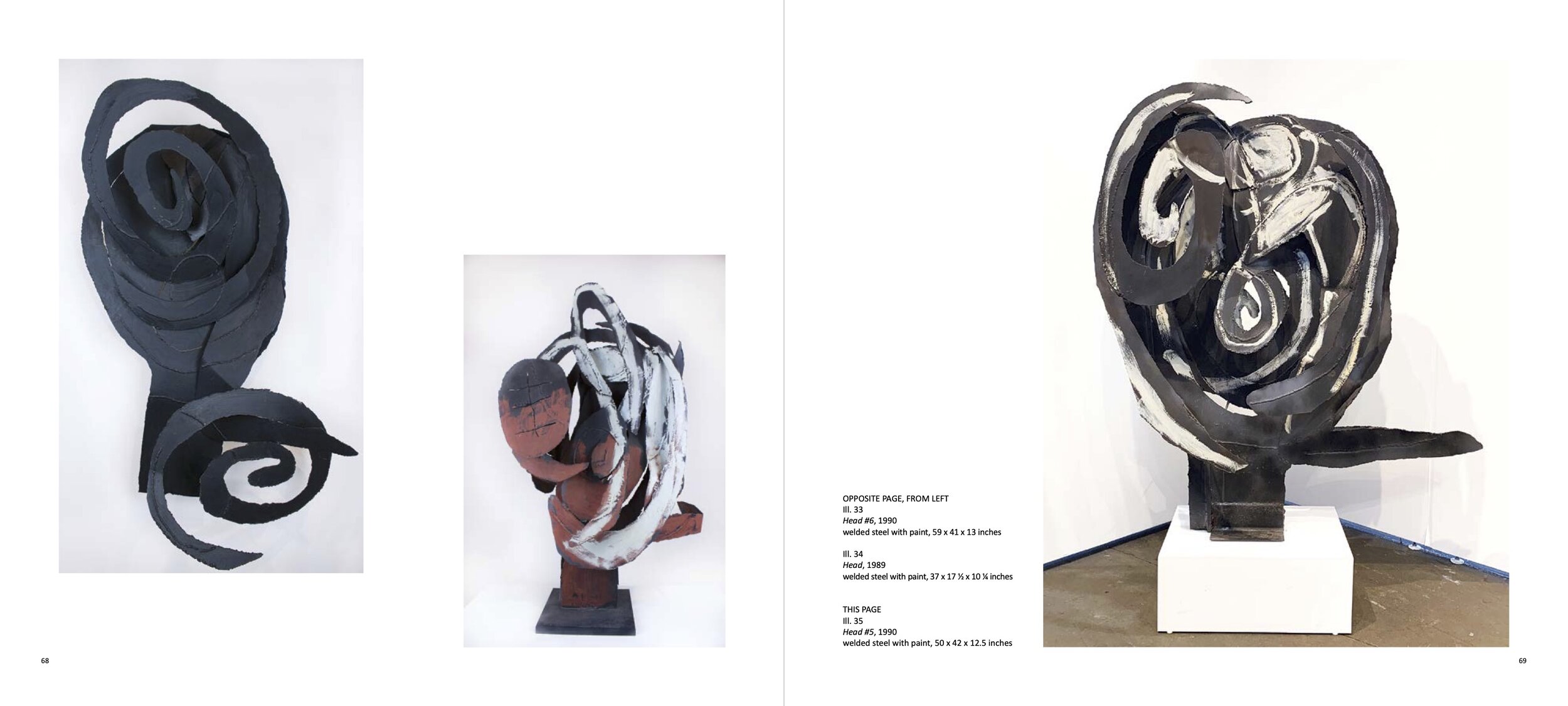

The artist continued working on metal sculptures at Grapa throughout 1989 and into 1990. He worked from templates with a welder, using the cutting torch as if it were a brush to delineate lines, sometimes adding color to the surface with a brush, sometimes painting it flat black. Head (1989) (Ill. 34) and Head #5 (1990) (Ill. 35) feature the head motif and depict the kneeling artist in a supplicant position that evokes prayer or a state of transience or grace. The supplicant figure is placed against, merged with, or emanating from a spiral that doubles as a phallus, symbolizing creation and destruction, a beginning or an end.

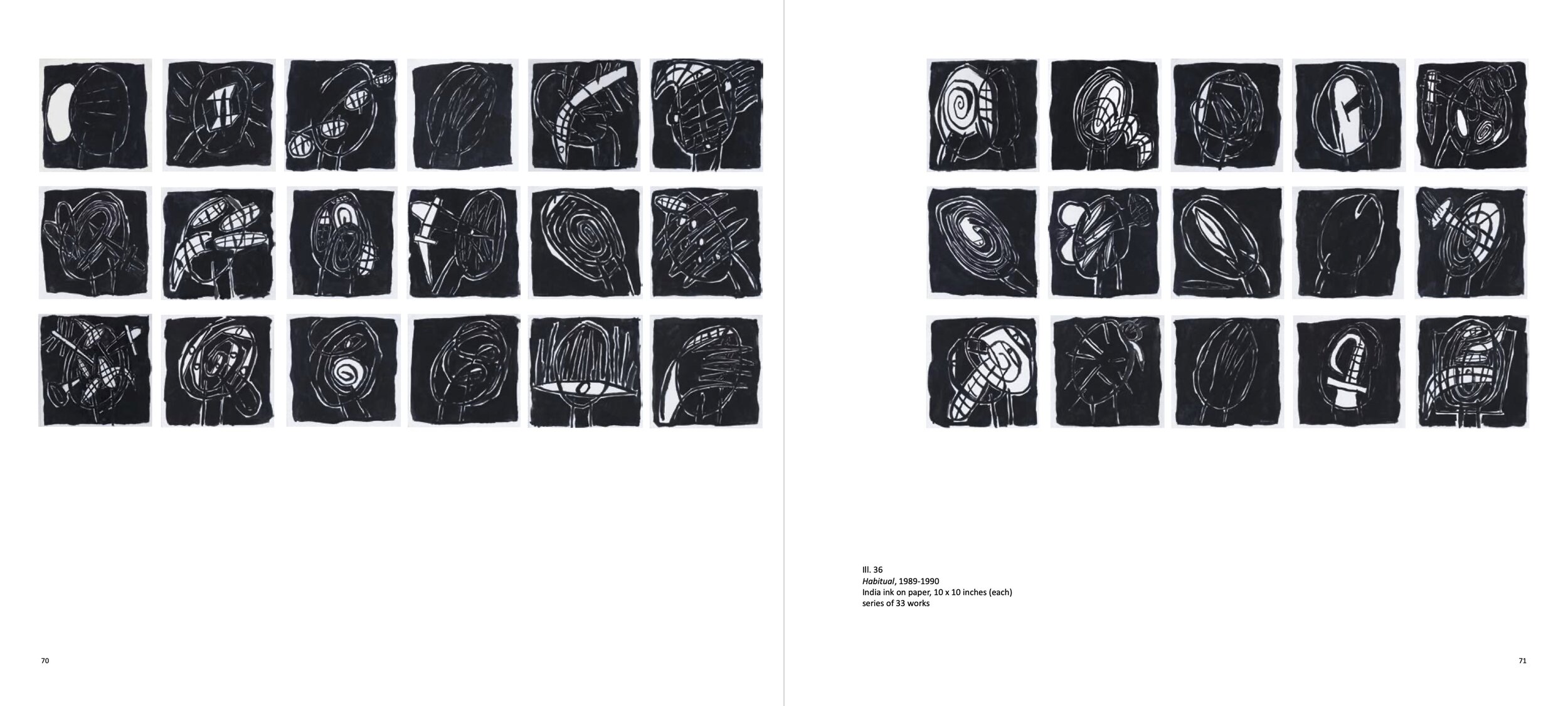

Habitual began as a series of ink on paper drawings in 1989. Thirty drawings were exhibited in Carlos Alfonzo: New Work, at the Bass Museum in September 1990. Following the exhibition, the artist and his close friend and designer Peter Menéndez decided to publish the drawings in book form. Habitual (Ill. 36) is composed of thirty-three drawings, twenty-six were published in book form with phrases in Spanish at the top of the page. All the phrases form a poem that is written in English at the end of the book. The book is dedicated to the memory of Farinelli (Carlo Broschi), a celebrated Italian castrato singer of the eighteenth century, who was one of the greatest singers in the history of opera.[67] Evidently, the impulse behind composing the book of images with phrases was motivated by his personal feelings regarding the relationship between the visual and the poetic.[68] Alfonzo greatly admired poets and had written poetry, as has been discussed in his earlier work. However, the artist never saw himself as a poet, but through poetry he tried to understand other ways of seeing. He expressed his thoughts on poetry this way: “I think that poetry is so visual, so musical, so richly expressive, and at the same time so hermetic. I really like that about poetry. I have never been able to write a good poem, but I do appreciate reading a good book of poetry.”[69]

1990: Finality

In addressing the proximity of death, Alfonzo passionately expressed his inner self through the images of witnesses, supplicants (himself), cubes, partial figures, heads, daggers, and windows of light. In a panoply of swirling lines, superimposed figures, and darker colors and tonalities, Alfonzo’s late paintings affirm the inner struggles the artist expressed in his final work. He was diagnosed with a low white-blood- cell count in November, hospitalized in December, and again in February of 1991. All the work Alfonzo produced during 1990 brought to creation the struggles between life and death—a crack in everything was how the light got in.

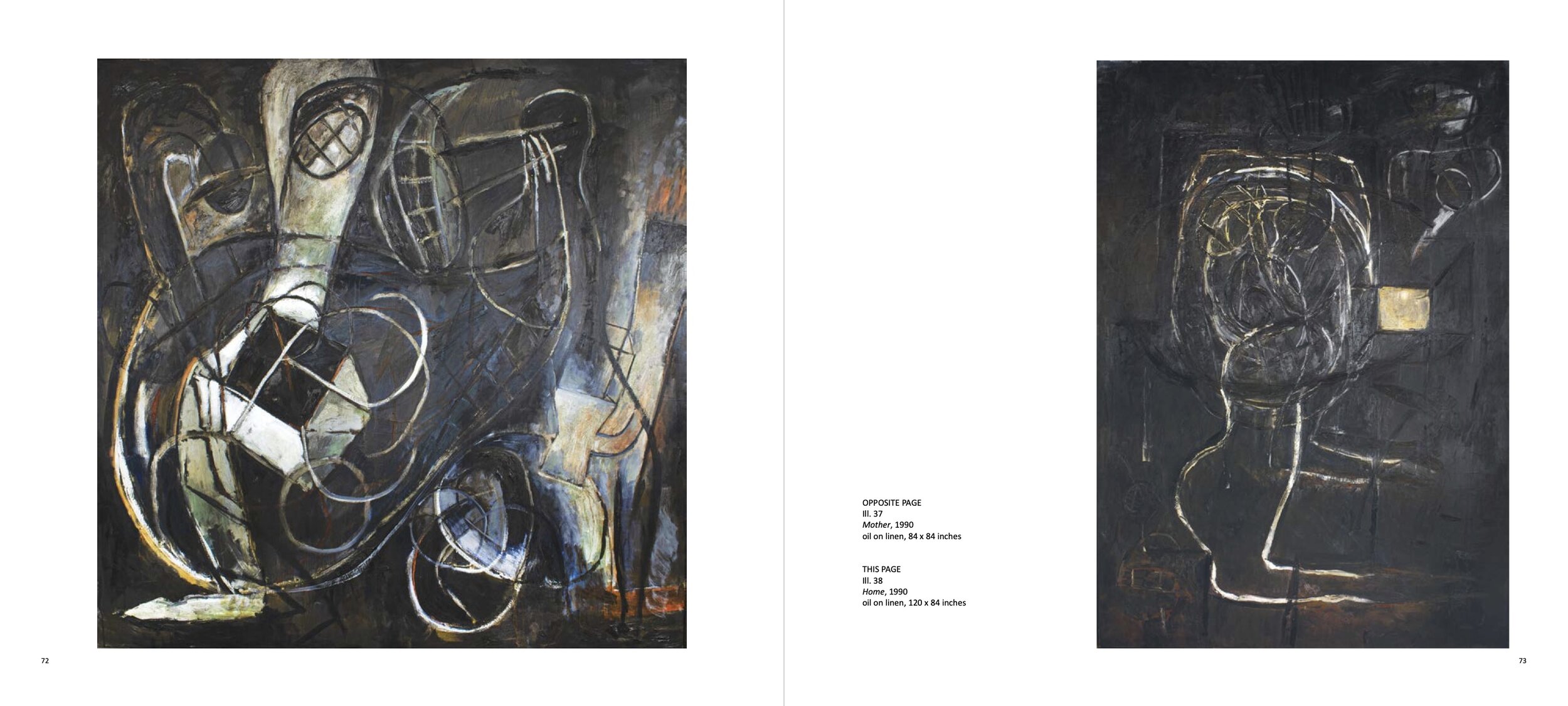

The painting, Mother, is an homage to his own mother, who had come to visit him from Havana earlier that year. She brought her son news that his father had passed away. (Ill. 37) In response to learning of his father’s demise, he did a painting, titled Father. Both paintings by him were included in the exhibition at the Bass Museum of Art in September.[70] Home, on the cover of the exhibition catalogue, may have been inspired by his mother’s visit; it was just as likely motivated by his own sense of mortality. (Ill. 38) The subject of home suggests rootedness and belonging; it is an external place as much as an internal concept and emotional state. Among the kneeling figures, the one outlined in white in the center of the composition appears to be pregnant. Her enlarged abdomen suggests a nascent life, one at the opposite extreme from the artist’s own. The female figure is rendered against the delicately drawn lines of an upside-down witness. The conflation of a pregnant figure, together with a witness, creates a sense of double fragility. The small hollow cube to the right of the spiral head refers to creation. One side of the cube is painted white, literally and metaphorically illuminating the scene in addition to providing an exit from darkness.

Alfonzo’s exhibition at the Bass had extraordinary meaning for him. He expressed himself to me in the following way: “A note to invite you to this show. I think it will be a beautiful – and strange – one. When I look at this work, for the first time, I see my marks, but now I also see me. It is very frightening but wonderful.”[71]

Unspeakable (Fig. 16) and Untitled [Blue Figure] (Fig. 15) are two interrelated works that in significant ways sum up the final thematic, conceptual, and emotional states of the artist as he was bidding adieu to work and life. Unspeakable defines the ineffable, the unimaginable physical and mental conditions of Carlos Alfonzo precisely when he was trying to come to terms with human existence: with life, death, fate, and solitude. He achieved a state of earthly transition in Unspeakable through the witnesses, the large dagger, the cubes; one inside of a cube and another illuminated with sun-like yellow, the same color as the swirling outlines of the large, centrally positioned figure, the artist! All the interconnected lines remind one of the continual drawings of the exquisite corpse (cadre exquis). Whereas Unspeakable is the more elaborately rendered painting, Untitled [Blue Figure] is more minimal. Stripped of most of the swirling, superimposed lines and recognizable elements of Unspeakable, Untitled [Blue Figure] speaks to us as one body, one person, one soul. The central figure (read Alfonzo) is a standing supplicant with his head slightly bowed. The swirling lines define the figure encapsulating himself. Deeply spiritual, courageous, and moving. Alfonzo foresees his exit into what he perceives as the great unknown.

—Julia P. Herzberg, Ph.D..©

ILLUSTRATIONS

NOTES

1. “A Boatlift Refugee Rides High,” People (March 1990), n/p.

2. For a comprehensive curriculum vitae in the extensive literature on the artist, see pages 74-77 of this catalog and the LnS Gallery website. Also see “Exhibitions,” in Triumph of the Spirit: Carlos Alfonzo A Survey 1975 – 1991 (Miami: Miami Museum of Art, 1997), pp. 155-158. The exhibition research was compiled by Stephanie Jacoby and Amy Rosenbaum with additional research provided by Peter Menéndez.

3. I am grateful to Anna Veltfort Valeton, who lived in Havana from 1962 to 1972 and studied at the School of Arts and Letters at the University of Havana from 1964 to her graduation in 1972. Since we do not know the courses Alfonzo took, her curricula are useful for the range of studies that provide us with an inkling of what was offered. Ms. Veltfort noted that the first three years of the “carrera” consisted of general humanities courses, as well as the obligatory classes in Marxism. She felt she received a solid background in Western culture and in the history of art of the first half of the 20th century, in which all the “isms” of modern art were taught. She suspects that the curriculum did not change much from 1972 through 1977 during Alfonzo’s years. She also noted that the professors, who were educated before the Revolution either in Cuba or the United States, were “top-notch in their respective fields.”

4. For an excellent essay on the artist’s biography, including an enumeration of his different teaching assignments, see Olga Viso, “Two Currents: The Life and Work of Carlos Alfonzo,” in Triumph of the Spirit, p. 24, n. 6. Hereafter referred to as MAM.

5. In Cuba, Alfonzo told José Bedia that he liked Klee, among other artists. Conversation with Bedia, July 25, 2006.

6. Como una vieja estampa of 1975 is illustrated in the MAM catalogue, p. 8. The artist wrote “Texto Nicolás Guillén,” on the bottom left under the verse “y ya te estás borrando como un dibujo antiguo.” The artist signed the work on the bottom right: “Carlos José 75.” Only the first of the two verses of Nicolás Guillén’s poem, “Your Memory,” written in 1927, is reproduced on the opposite page of the drawing. The same first verse of the poem by Guillén was reproduced in the 1976 catalogue brochure. Another ink- on-paper drawing, titled Dibujo y Transfiguro, is in the MAM catalogue but curiously is not on the checklist of the original brochure. Perhaps its absence was an oversight, or perhaps the artist executed it after the exhibition at the Amelia Peláez Gallery. Another drawing, titled Surface, was rendered in the same style as the other drawings in Como una vieja estampa. Surface is dated 1979 and listed as No. 4 in Carlos Alfonzo: Development of an Artist: An exhibition of paintings, drawings and ceramics at the Bacardi Art Gallery, 6 May to 3 June 1989. On stylistic grounds, it belongs to the 1976 series.

7. Nueva trova is a movement in Cuban music that emerged around 1967– 68. It combines traditional folk music idioms with progressive and often politicized lyrics.

8. Translation is by the author.

9. I am extremely appreciative to Margarita González Lorente, curator of contemporary art, El Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Havana, for finding this catalogue and sharing the contents with me. Email communication, October 31, 2019.

10. There were many works of art by Wifredo Lam that Alfonzo could have seen either in slides during courses on Cuban art or at the National Museum of Fine Arts / Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes.

11. For background on the socio-political-economic events in Cuba in 1979 into 1980, see Victor Andres Triay, The Mariel Boatlift: A Cuban-American Journey (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 2019), pp. 23, 24, 25. Hereafter referred to as Triay.

12. Fors remembers that Alfonzo showed two small works. Rubén Torres Llorca remembers that the authorities questioned his motives for having participated in a private exhibition. He remembers the conversation as a negative one. Fors, on the other hand, remembers their questioning as having no important consequences. Conversations with each artist during October 2019.

13. Emilio Rodríguez sent me the cover of the announcement from the exhibition via Messenger, November 14, 2019.

14. Fors told me that Alfonzo never picked up his two works. Nor did he attend the evening’s opening at Fors’ home, although he went to the exhibition in Cienfuegos. Telephone conversation, Miami, October 30, 2019.

15. For a close analysis of Volumen I, see Luis Camnitzer, New Art of Cuba (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1994), ch. 1.

16. Conversations with Rubén Torres Llorca, October 29, 2019.

17. Triay, pp. 23, 24. Also see Mirta A. Ojito, Finding Mañana: A Memoir of a Cuban Exodus (Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan, 2005.)

18. Triay for discussion on the regime’s rules on artistic matters and homosexuality, p. 15.

19. Ibid., pp. 25-26.

20. Ibid., pp. 35-36.

21. In email exchanges with Gory, he related his father’s account of his medical interventions with Alfonzo in the embassy. Gory’s father, a close friend of Alfonzo’s mother, had known her son since he was a young boy. Gory remembers his father’s account of the security agents who infiltrated the embassy and mistreated the asylum seekers, many of whom, including Alfonzo, became destabilized. The artist avoided a return to the embassy because of Dr. Jorge López Valdés’ assistance and therefore avoided a repetition of the mental and physical abuses he otherwise would have suffered. Email October 23, 2019.

22. Triay’s accounts of the people he interviewed recall vividly how and when the Cubans received safe conduct visas in the embassy; how they were ushered out in buses, driven through throngs of people who screamed at them, and often hit them with rocks and sticks.

23. Ibid., p. 145

24. Ibid., p. 146.

25. Julia P. Herzberg, “Conversations with Carlos Alfonzo,” in MAM, p. 125. Hereafter referred to as “Conversations,” in MAM.

26. Ibid., p. 125.

27. According to María Elena Mena, a friend from Cuba, the artist called her when he first arrived in Miami and went to her home, where he stayed for a short time. Telephone communication with Sergio Cernuda, October 26, 2019.

28. “Conversations,” in MAM, p. 126.

29. Alfonzo and his wife married when they were young, and then separated. However, he often stayed at his wife’s home that was on the same block as the artist’s parents’ home. Viso, MAM, p. 24, note 7.

30. Giulio Blanc, one of the seminal art historians, curators, and critics on Cuban art brought early and sustained attention to Alfonzo in different stages of his development. Blanc included and illustrated Song to My Son, on the cover of the small brochure for Cuban Fantasies, at the Kouros Gallery in New York, in Winter 1983. Good-Bye is illustrated in MAM, p. 80.

31. Llamada a La Habana (Call to Havana) is illustrated in MAM, p. 82.

32. The INTAR GALLERY of LATIN AMERICAN ART was one of a few venues for Latino/a, Latin American or Hispanic artists living in New York. Giulio Blanc introduced Lockpez to Alfonzo’s work.

33. I thank Ramiro A. Fernández for informing me that Alfonzo stayed at his apartment during his visit to New York in both 1982 and 1988. Email October 21, 2019.

34. “Conversations,” in MAM, p. 132.

35. In all probability, the funds from the CINTAS Fellowship arrived while the artist was in Los Angeles, which might explain how he was able to rent a garage where he could paint in a larger format.

36. Last Tears is illustrated in MAM, p. 84; Red Downtown Judy, p. 89, and Untitled [Planes], p. 86.

37. “Conversations,” in MAM, p. 126.

38. Julia P. Herzberg, “Excerpts from a Conversation with Carlos Alfonzo and César Trasobares,” in MAM, p. 134. Hereafter referred to as “Excerpts” in MAM. César Trasobares and Craig Robins conducted a videotaped interview with the artist in November 1990. In editing the excerpts from raw footage, I have used the artist’s words whenever possible in order to retain Alfonzo’s own idiomatic expressiveness while communicating his intended meaning.

39. Percy Steinhart, telephone communication, November 13, 2019.

40. Petty Joy is illustrated in Hispanic Art in the United States: Thirty Contemporary Painters & Sculptors (Abbeyville Press, Inc., 1987), p. 70. Curators and essayists, John Beardsley and Jane Livingston. Hereafter referred to as Hispanic Art in the United States.

41. The Biltmore Hotel had a formal exhibition space in the ballroom with an active exhibition program. The director/curator Arnold Lehman later became the director of the Brooklyn Museum. Giulio Blanc curated the exhibition and wrote a short text in the brochure.

42. Trail is illustrated in “Hispanic Art in the United States,” p. 136.

43. “Conversations,” in MAM, p. 129.

44. Santería is an Afro-Cuban religion that has evolved from West African, mainly Yoruba, beliefs.

45. “Hispanic Art,” p. 137. This thought dovetails with artists’ comments to me in “Conversations” in MAM, pp. 127-128.

46. “Excerpts,” in MAM, p. 132.

47. “Conversations,” in MAM, p. 129.

48. Toured Rome and Bologna with Giulio Blanc, who was temporarily living in Rome. Then Alfonzo traveled to Florence and Venice on his own. See Olga Viso in MAM, p. 37, note 43 letter to Giulio Blanc.

49. “Conversations,” in MAM, p. 128.

50. The artist was critically acknowledged in the following exhibitions for his wide-ranging subject matter and the platforms from which he spoke to identity. These include, among others, his relationship to Afro-Cuban and Caribbean expressions, in Caribbean Art/ African Currents at the Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art, New York (April 17 – May 25, 1986); his expatriate status, in Expatriates: Paintings by 15 Young Latin American Artist (April 27 – May 20, 1986); his printmaking, in Hot Off the Press: Monoprints in the Barbara Gillman Gallery in Miami (October 6 – November 3, 1986); his public art work, in Public Art Process: Art Exhibition of Drawings, Models and Photographs / Metro- Dade Art in Public Places Collection 1973–1985; and his place as a Latin American abstract artist, in Abstraction: Four from Latin America at Frances Wolfson Art Gallery, Miami-Dade Community College (Oct. 9 – Nov. 7, 1986).

51. “Conversations,” in MAM, p. 128.

52. Santa Lucía has not been exhibited since Sheldon Lurie’s exhibition, “The Art of Carlos Alfonzo,” in 1988.

53. During the AIDS crisis of the 1980s and 1990s, the homoerotic icon Saint Sebastian was widely invoked to embody the suffering and persecution of people with AIDS. See caption for Gerardo Velázquez’ (b. 1958, Mexico; d. 1992, Los Angeles), The Neglected Martyr, 1990, at Williams College Museum of Art in the exhibition Axis Mundo: Quee Networks in Chicano L.A. Major attention is given to the work of queer artists who died of AIDS in the exhibition catalogue by Ondine Chavoya and David Evans Frantz, et al., in Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A. (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art and ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries and Del Monico Books/ Prestel, 2018).

54. Alfonzo said that he felt there were many artists within him and that he got ideas from other artists. He realized that he had to select the strongest artist within himself and that he could allow other artists to meet with him and have an ongoing interchange of ideas. “Excerpts” in MAM, p. 132.

55. Carlos Artigas dressed his lover and partner in the coffin with the t-shirt Alfonzo had designed. Artigas crossed Alfonzo’s arms over his chest and put a rose between the hands as the Rosicrucian’s emblem to carry on into the beyond.

56. Many artists had already addressed AIDS in the 1980s, among them Sue Coe, David Wojnarowicz, Keith Haring, Félix González-Torres, Martin Wong, and Luis Frangella. By the end of 1987, 40,849 deaths had been reported. That same year, the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) was founded in New York. Their slogan “Silence=Death” was coined. In 1987, President Reagan first mentioned the word “AIDS.” Azidothymidine (AZT) became the first anti-HIV drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

57. The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden has both Study No. 2 in their collection and The Dark Night, 1988-89.

58. Pablo Cano fondly remembers Barbara Greene, who gave Alfonzo and him an exhibition, Carlos Alfonzo, Pablo Cano: New Work, in 1987 in her tiny gallery on Rice Street in Coconut Grove. That gallery developed into one of the most coveted gallery spaces of the late 1980s. Many in her local stable of artists died of AIDS by the mid-1990s. Email communication, November 5, 2019.

59. “Conversations,” in MAM, p. 129.

60. As early as 1977 in Experimentos de Carlos José Alfonzo at the Pequeño Salón, the artist showed eight works in terracotta.

61. In my conversation with the artist during his exhibition Carlos Alfonzo: Paintings, at the Osuna Gallery in Washington, DC in November 1988, he said that there were a few contemporary artists, such as Francesco Clemente, Mimmo Paladino, and, more recently, Lucien Freud in whose work he “sensed a mystical atmosphere.” With regard to Paladino, I intuit that Alfonzo appreciated the ways in which Paladino expressed psychological states and layered ideas, references, and symbols in his images. See “A Conversation with Carlos Alfonzo,” Review: Latin American Literature and Arts. New York: The Americas Society (Jan. – June 1989): pp. 5-10. This particular reference is in “Conversations,” in MAM, p. 127.

62. César Trasobares’s text, “Carlos Alfonzo Clay Works and Painted Ceramics,” in the exhibition brochure Carlos Alfonzo: Clay Works and Painted Ceramics (Miami: Pérez Art Museum, 2015), is an excellent overview of the forms, materials, iconography, and series of small and also monumental ceramic works. The text also addresses the artist’s ambitions for public works, never realized, as well as the two public murals: Ceremony of the Tropics (1986), for the Santa Clara Metrorail Station, and Brainstorm (1991), installed on the pedestrian bridge at the Engineering and Computer Science Building at Florida International University.

63. Ballerinas have been in the artist’s iconographic repertory since at least Untitled [Ballerinas with Dumbbells] and Sea Bitch Born Deep, both of 1986.

64. Alicia Alonso, whom Alfonzo knew in Cuba, was the Cuban prima ballerina and choreographer whose company became the Ballet Nacional de Cuba in 1955. Alfonzo wrote Stabbed Tongue Ballerina (homage to Alicia Alonso) on the back of the painted glazed ceramic work of 1986.

65. “Excerpts,” in MAM, pp. 131, 132.

66. There were three significant exhibitions that Alfonzo participated in early 1988 aside from his solo exhibition at the Lannan. They were Carlos Alfonzo New Work at the Greene Gallery (April 8 – May 11); Carlos Alfonzo: Development of an Artist, 1976 – 1988 at the Bacardi Gallery (April 22 – June 3) and Hispanic Art in the United States at the Lowe Art Museum (April 7). (Fig. 17)

67. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Farinelli. Accessed on December 4, 2019.

68. The book also provided a vehicle for the artist to publish his drawings.

69. “Excerpts,” in MAM, p. 132.

70. For that exhibition, Giulio Blanc wrote an essay, “Carlos Alfonzo’s Black Paintings,” a descriptive that still resonates among Alfonzo researchers.

71. Carlos sent me an invitation to his exhibition at the Bass Museum, with a personal handwritten message dated 9-11-90. He addressed it “Dear Julia,” and ended with “I will send you a catalog as soon as possible and a copy of my drawings ‘Habitual.’ Again, thanks for your interest in my work and your valuable writings about it. Your friend, Carlos Alfonzo.” His exchange was very meaningful because it spoke to a new body of work that he had told me about earlier in 1990, before I had selected two paintings for The Decade Show: Frameworks of Identity in the 1980s. Those works, collaboratively approved by the three other curators, were Feast of Wrath (1983) and Gulfstream (1988). Alfonzo’s paintings were installed in the Museum of Contemporary Hispanic Art (MoCHA) in New York (May 12 – August 19, 1990). He was unable to attend the exhibition.

I appreciate receiving permission from the LnS Gallery in Miami to reprint the catalogue Witnessing Perpetuity: Carlos Alfonzo. Photos © Andrea Sofía Rodriguez Matos

Gallery image: Carlos Alfonzo, Untitled (Blue Figure), 1980. ©Juan Loumiet.

Gallery website: https://lnsgallery.com/carlos_alfonzo/

![“Witnessing Perpetuity: Carlos Alfonzo,” exhibition catalogue, LnS Gallery, Miami, 2020. [Ill. 16]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5f9d77a44195e1765429242c/1604786993119-GSZDIANWDBFIE4ABGO1D/_Carlos+Alfonzo.jpg)