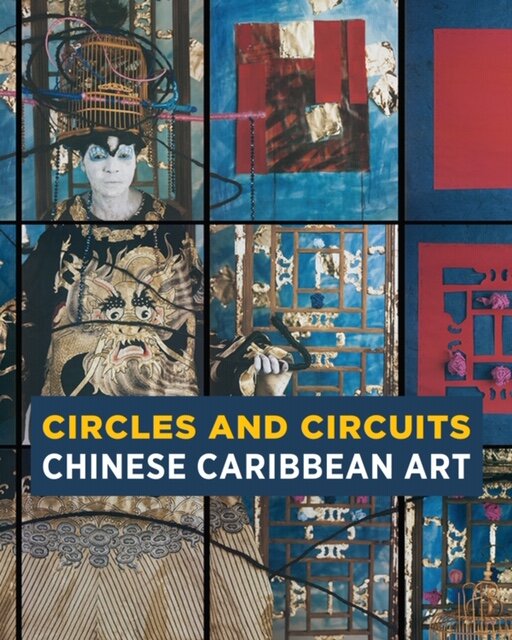

Cover, exhibition catalog, Circles and Circuits: Chinese Caribbean Art, 2017.

PAST – PRESENT: Conversations with Maria Lau and Katarina Wong

Julia P. Herzberg

The following conversations with Maria Lau and Katarina Wong fall within the framework of oral histories, giving voice to unique perspectives of similar—yet distinctive—family backgrounds and migratory experiences. Both of the artists were born in the US, while their parents originated from different countries. Their mothers were Cuban-born with Spanish ancestry and their fathers were of mixed Chinese heritage: Lau’s father was born in Cuba to a Chinese father and a Cuban mother, while Wong’s father immigrated to San Francisco from China around 1939. Lau’s family came from Cuba to the US on a Freedom Flight in 1970; Wong’s parents met and married in the US. Their respective narratives speak to memories of growing up in the States and their relationships to family backgrounds in which ethnic, cultural, linguistic, and social factors defined them in significant ways. These conversations provide us with keen insights into the communities where they were raised, the impact of their many trips to Cuba (where they connected with their extended Cuban families and their Chinese lineage), their university studies, and the content, sources, processes, and mediums of their artwork.

Since 1997 Lau has photographed people and places in both rural and urban areas of Cuba, including Havana’s Chinatown. She initially intended to use the photographs as reminders of the visual richness of the island country, but soon these visual recordings became the basis of an ongoing photographic project using in-camera multiple exposures and infrared film. On one of her trips she went to the Chinese Associations in Havana to learn more about her Chinese ancestry. These visits led to our discussion of her multimedia documentary series titled 71.

It was during frequent trips to Cuba in the late 1990s that Wong “discovered” Havana’s Chinatown and its diasporic Chinese community. These encounters instigated a reconsideration of her cultural and ethnic lineages—Cuban, Chinese, and American—as intertwined. As a sculptor and painter her work references Chinese imagery, subjects from Western art, and memories of people, events, and places in Cuba and the United States.

The distinguished bodies of work by Lau and Wong presented in this exhibition are dialogues with their hybrid, multifaceted heritages. Both conversations will resonate with readers who have family from different countries, who speak different languages, and who find common ground through familial ties and mutual respect for cultural differences. Ultimately, Maria Lau and Katarina Wong seek connections across geographical, historical, linguistic, and racial divides, and use those divisions to connect their art to their lives. Their personal histories traverse borders, speaking eloquently to the ways in which belonging and identity find singular paths.

Maria Lau in Conversation

Fig. 1. Maria Lau, Untitled (detail), 2014, digital chromogenic color print. Courtesy of the artist.

Julia P. Herzberg: We have talked about your having been born in New Jersey to a Cuban mother of Spanish ancestry and a Chinese Cuban father with ancestry from Guangdong. Where were your parents’ families from and when did they come to Cuba? Tell us about their backgrounds.

Maria Lau: I don’t know where my maternal grandparents were from in Spain, or when they immigrated to Cuba, but my paternal grandfather was born in Guangdong (China) in 1899 and went to Cuba in 1916. His brother, my great-uncle Boyu Lau, preceded him to Cuba and ran a general store in Matanzas where my grandfather worked. At some point Boyu decided to leave Cuba and return to China for good. My grandfather then moved to Pinar del Río, opened a general store and married my Cuban grandmother. My father, who was born and raised in Cuba, never learned to speak Chinese or Cantonese. Our family’s common language was Spanish.

JPH: When did your parents leave Cuba?

ML: My parents left Cuba in 1970 for political reasons, with their three sons and my maternal grandparents. They waited several years before they were given visas to leave Cuba. When they were finally granted permission from the government, however, my father had to leave his only brother, Santiago, behind. My family left on a Freedom Flight (or as they were called in Spanish, los vuelos de la libertad). Those flights to the US ended in 1973. When we arrived in Miami my mother’s cousin sponsored the family, and in 1970 we moved to New Jersey, where I was born.

JPH: Let’s talk about growing up in Jersey City in a bilingual, multicultural family. Did your grandparents instill their Cuban identity in your family?

ML: My family consisted of my parents, my four brothers, and my maternal grandparents. My parents worked full-time, so my grandparents took care of us. I have very wonderful memories of my grandparents. In particular, I remember the rich flavors of Cuban food in my grandmother’s kitchen. In later years she gave me tips on how to cook Cuban dishes. I will also always remember her listening to Spanish music and Cuban comedy on the radio while she cooked.

My grandfather was a stern man who made sure we observed both Cuban and American traditions, especially during the Christmas holidays. We went to Christmas Eve mass and celebrated Three Kings Day on January 6. Both my grandparents made sure to remind us of the importance of being bilingual and multicultural, assets they perceived as being important in society.

Even though we younger ones spoke English among ourselves, my parents and grandparents spoke Spanish at home, and we primarily identified as Cuban Americans. I would say that my father—who kept close ties with his Cuban Chinese brother in Pinar del Río—identified more with his Cuban heritage because his father traveled for long periods to China while he was growing up.

JPH: How did family separation affect you while you were growing up?

ML: Family separation, due to the political events in Cuba, was emotionally difficult to deal with growing up. When I was in college I decided I wanted to learn more about Cuban history, so I pursued a degree in history with a specialization in Latin American and Caribbean studies at the City University of New York (CUNY). There I met Gerardo Renique, a professor who helped guide my studies in those areas. We remained in contact after I left CUNY, and he was aware of my photography work in Cuba. We talked about my familial experiences there, and he encouraged me to investigate and document my personal history regarding my Chinese heritage. In 2003, he invited me to speak about my ancestry to a class he was teaching on the Chinese diaspora in the Americas. Instead, I made a visual presentation, a narrated video detailing my search for my Chinese ancestry along with my photography. He liked it so much that he in turn showed it at the Overseas Chinese Conference in Havana in 2003, at which time he introduced the story of 71 to the Cuban Chinese audience. As a result of the video presentation, I was invited to exhibit at Casa de Arte y Tradiciones China in Havana’s Chinatown in 2003.

JPH: You have told me that during your first trip to Cuba in 1997, you were so impressed with the people and scenes of the surrounding rural and urban areas that you decided to photograph them. Tell us about the processes you used.

ML: I began using infrared film in my first photography class at CUNY in 1995. I once told my photography professor that I had a haunting dream of a woman wearing a white dress who was running through a field of pink hay. He told me that I should look into using infrared film (primarily used for scientific photography) that could render effects similar to those I dreamed. While studying photography as an undergraduate, I learned everything I could on my own about using infrared film in both color and black and white.

On my first trip to Cuba in 1997, I carried two cameras. One was loaded with color (or black-and-white) film, the second with infrared film. I used my primary camera to record a moment in time, but my secondary camera recorded hazy, grainy, dream-like scenes, as if they were an alternate reality. The scenes I took with infrared film project gave a sense of what I imagined Cuba was like when I was growing up as a child.

JPH: Where did you travel in Cuba during your first trip?

ML: I was going there specifically to meet my Cuban Chinese relatives: my uncle Santiago and my two cousins. I traveled to Havana and then made my way to Pinar del Río. During my time at my uncle’s house, he mentioned that some of my mannerisms reminded him of his father, my Chinese grandfather. Uncle Santiago also told me about my grandfather’s first family, whom he had left behind in China. My grandfather kept in touch with his two daughters from his first marriages and sent remittances regularly during the years he lived in Cuba. In 1972, his dying wish was to send one last letter with a remittance to his daughters in China. That telegram was also intended to inform them of his passing. My uncle fulfilled his father’s instructions, but he never heard back from his half-sisters in China. Since communication to and from Cuba during the 1970s was especially difficult, Uncle Santiago was concerned that they had never received their father’s last wish, and asked me if I could use my available resources to find his half-sisters when I got back to the United States. I told him that I would try.

JPH: Tell me about your second trip to Cuba. How did you go about trying to find your aunts?

ML: Between 2000 and 2003, I traveled to Cuba once a year to see my family and research my Chinese ancestry. In order to find my Chinese aunts I needed more information on my grandfather, so I started looking into his records in order to identify the original birth names of his daughters, since if my aunts were married their last names would have changed. Therefore, I visited Barrio Chino in Havana with the hope of finding more information about my grandfather.

Fig. 2. Maria Lau, Kwong Wah Po, (from 71 series), 2009, digital chromogenic color print, 16 in. x 24 in. Courtesy of the artist.

I was assisted by three of the Chinese associations in Havana’s Chinatown: Casino Chung Wah, Min Chi Tang, and Lung Kong. These associations, among others, are registered with the Cuban government and are listed as Sociedades Chinas de instruccion y recreo y union familiar. These associations are organized through family surnames, and offer their members a number of social and professional services. They also assist in maintaining transnational ties. The main association under which all other Chinese associations operate is the Casino Chung Wah, informally known as Centro Nacional de Centro Chino. The president of the Casino Chung Wah did not have any information on my grandfather, nor did the association Min Chi Tang. Since my last name is Lau, I belong to the Lung Kong association, so the president of the Casino Chung Wah advised me to visit there.

In between meetings with association leaders, I photographed street scenes of Havana’s Chinatown with the objective of documenting the Chinese community that remained after the mass migrations out of Cuba as a result of the 1959 revolution. Chinatown had become a fragment of what it used to be, when it once occupied some forty-four blocks and was considered the largest Chinatown in the Americas. Among the scenes I captured were vintage American or European cars on worn streets and vacant sidewalks that decades ago bustled with activity and thriving businesses. When I was there, Chinatown was under restoration and looked like a dusty ghost town. The plaques on the buildings were the only indication of the Chinese community there.

The photo Kwong Wah Po features a sleek black car with the sign of the last Chinese language newspaper in Cuba superimposed on the hood. (Fig. 2) It was important to capture the juxtaposition of the well-preserved car and the image of the name of the newspaper (Diario Popular Chino) that was published infrequently because workers no longer knew how to typeset Chinese characters.

Fig. 3. Maria Lau, (left) Dad Divination, 2003, digital chromogenic color print, 29.75 in. x 27.125 in.; (center) Tai Pai, 2003, digital chromogenic color print, 19.75 in. x 29.75 in.; (right) Untitled, 2014, digital chromogenic color print, 19.75 in. x 29.75 in. Courtesy of the artist. Installation view in Circles and Circuits II: Contemporary Chinese Caribbean Art. Photo by Ian Byers-Gamber.

JPH: That image, as well as others you have photographed, is significant from a historical standpoint as an artifact of a vanishing period now almost gone.

ML: Yes, my photographs of Chinatown are fragments of a historical narrative between the Chinese community that once populated the area, and the dramatic decline during the years I was there.

JPH: What were your experiences at the different associations in Havana, particularly at the Lung Kong association?

ML: The Lung Kong treasurer welcomed me as a Lau and told me that the association was my home. He took me to a room with an altar imported from China some time ago. He asked me to approach the altar, where the fortune sticks were in a receptacle. He then directed me to ask my ancestors a question, and afterwards to pick out a stick. In my supplication, I asked my grandfather to help me and assure me that I was on the right path. When I chose the divination stick, the number 71 was written on it. That number was significant because it connected me to my grandfather and father. Coincidentally, 71 was once the number of my street address—the house my father bought to raise our family— and it is also the year I was born.

JPH: Indeed, the number 71 turned out to be very fortuitous! Tell us how your 71 series has evolved over the years.

ML: In 2003, I was invited by Havana’s Grupo Promotor del Barrio Chino to exhibit at La Casa de Arte y Tradiciones for the Festival de las Comunidades Chinas de Ultramar. There I showed a few of the 71 photographs and a short narrated video about the search for my aunts.

During the ten-year period (2003 to 20013) that I have worked on and shown the artwork of 71, the exhibits have featured photographs recording various stages of my family search. The first photographic series, 71 A Cuban Chinese Dream, was about my first trips to Cuba and the intent of finding my aunts. The second series, 71 Fragments of a Dream, added additional photography and the aforementioned video, but my search remained unfulfilled. The third series, 71 Memory and Identity, told the story of finding my aunts, and the journey I took to unite my family. Each exhibit built upon the imagery of previous exhibits. I added more photographs, created installations, and incorporated archival documents gathered over the years.

Fig. 4. Maria Lau, Chinese Car (from 71 series), 2003, digital chromogenic color print, 60 in. x 81 in. Courtesy of the artist.

JPH: You have talked about your efforts to connect with your aunts from China, your father’s half-sisters. How did you accomplish this?

ML: In 2006 I located my Chinese aunts in San Francisco with the help of the Overseas Chinese Office at the Consulate General of China in New York, and in 2007 I went there to meet my aunts and their families. At that meeting I asked my aunts about my grandfather’s last remittance and letter, questions that finally gave my uncle Santiago peace of mind about the issue. I also gave one of my aunts a photo of my grandfather that I had brought from Cuba, after she told me she did not have any photos of him. Subsequently I attempted to maintain communication with both sides of the family through photos, letters, and emails.

In 2010, my uncle was allowed to travel to the US. I arranged for my father and uncle, now respectively in their 70s and 80s, to meet their two Chinese half-sisters for the first time in San Francisco. I took personal family photos and the event was momentous.

JPH: Let’s talk about the processes that you used in the 71 series.

ML: The major process I used for the 71 series was one of multiple exposures. (Fig. 3) I used two different types of multiple exposure techniques, digital and in-camera. After 2007, the exposures were digitally composed from film. Prior to that, all my multiple exposures were created in-camera with film. The process of creating in-camera multiple exposures leaves much of the resulting image to chance. For instance, the multi-exposure setting in

my camera would realign my exposures as I was creating them on the negative. I would shoot two horizontal scenes but sometimes it would make one vertical; or a portrait shot would be squeezed inside a rectangular silhouette from the prior exposure. The final result of using the multi-exposure setting was always a surprise, no matter how much I tried to control the outcome. To me, the experience of searching for my aunts and for information on my grandfather in Cuba was like that in-camera process. I had set intentions of what I wanted, but what actually happened was always a surprise. Having the creative process reflect my personal experience was important to me. Photography for me is not just technically capturing a moment; it’s a process, a style, and ultimately a story.

JPH: Let’s talk about two other iconic images from this series, Chinese Car and Dad Divination.

ML: Chinese Car (Fig. 4) features a 1950s American car and a superimposed image of the Wushu martial arts school that features the yin/yang symbol, the Chinese character Wushu, and two Chinese dragon figures. The Wushu school plays an important role in the revitalization of Chinese culture in Cuba by teaching martial arts, dance, and traditional Chinese exercise. The visual narrative of this photo is personal to me. I imagine seeing my own history and cultural identity intertwined in this photo. The American car, the Chinese yin/yang symbol, and the Cuban landscape combines all three cultures.

Dad Divination, the first photograph in the installation of my work at the Chinese American Museum, is a digital collage I created in 2003 from a photo I brought from Cuba of my father when he was about twenty years old. I love the old portrait-style photos that were taken at a studio and printed on warm-tone photo paper. I located a set of fortune sticks in New York and superimposed the two. The photo is an interpretation of the moment at the Lung Kong altar when I picked the number 71 and felt reassured by my grandfather that I was on the right path.

JPH: How did the 71 series segue into The Chinese Cuban Dream Book (La Charada China)? Furthermore, how we can better understand your adaptations and appropriations of La Charada China from artistic and popular cultural perspectives?

ML: During the years that I was exhibiting the work of 71, I met people that were moved by my story, and they began to share their personal histories with me. These interactions prompted my thinking about shared experiences, history, and larger narratives. La Charada China is a shared historical and cultural Chinese Cuban reference point that began sometime in the 1800s, when Chinese immigrants brought the symbolic numerical system to Cuba. The system of numbers originally ran from 1 to 36, where each number represented people, places, or things. The numbers and characters attempt to give meaning to everyday life events, dreams, and coincidences, as a language of the cosmos. The numbers are then used to play the national lottery. It’s a very popular game of luck and fortune distinctly linked to Chinese history and mysticism.

It was a natural transition for me to go from telling my own story to telling the stories of people who still use La Charada China as a means to interpret life via the number system. I’m currently in the research stage of the project and am gathering personal stories from interviews to create the photography for the images. I’m looking forward to visually creating a Cuban-Chinese-American narrative in different photographic mediums that is based on oral history, a fusion of cultures, and dreams.

Katarina Wong in Conversation

Fig. 1. Katarina Wong, Fingerprint Project: Murmuration Unfolding (detail), 2017, wax cast molds, sumi ink, and powdered graphite, dimensions variable, courtesy of the artist. Installation view in Circles and Circuits I: History and Art of the Chinese Caribbean Diaspora. Photo by Ian Byers- Gamber.

Julia P. Herzberg: How do your Chinese and Cuban backgrounds inform your sense of self? Katarina Wong: My mother is Cuban and my father Chinese. They were both immigrants to the US, so my sisters and I are the first generation in our family to be born and raised here. Although my parents were proud to be in the United States, they made sure we knew about their respective cultures when we were growing up.

JPH: How did your father find his way to the US?

KW: My father, Foon Ah Wong, came to the US when he was sixteen, in 1939. He was originally born and raised in a small village in the Guangzhou region. My grandfather came to the US illegally through Mexico when my dad was a small child. He made his way to San Francisco where he found work. He had to leave my grandmother behind because the Chinese Exclusion Act was in effect, and he wasn’t able to send for his son because he didn’t have his papers.[1] However, my grandfather asked a friend (who was a citizen) to claim my father as his son so he could go to San Francisco—a common practice at the time. After a stint in Angel Island, the West Coast equivalent to Ellis Island, my dad entered legally as my grandfather’s friend’s “paper son.” It was also how our family name, Liu, became Wong.

JPH: When did your mother come to the US and what were the circumstances of her immigration experience?

KW: My mother, Lucia Capin Urquiola, came to the US in 1960, about six months before relations were severed between the US and Cuba on January 3, 1961. Unlike most Cuban immigrants at that time, she didn’t come for political reasons. She came from Mantua (a small town in western Cuba), moved to Havana as a child, and as a young adult she yearned to travel. In her mid-twenties she had an opportunity to be a nanny in New York City, where she moved with the intention of saving money to return in a year. Unfortunately, once the borders closed she faced the difficult decision of staying in New York or returning to Cuba. Her father advised her to stay because he thought the political situation would soon change. Little did anyone know then that it would be nearly twenty years before they were reunited.

JPH: I know you were born in York, Pennsylvania where your father worked as a mechanical illustrator. What motivated your family to move to Naples, Florida in 1971?

KW: My dad got a job as a graphic designer at a local newspaper in Naples, which was predominantly white and affluent. We lived in a working-class neighborhood where the only other minority family I recall was the Irish American/Filipino family next door. Although I didn’t really have the vocabulary to express my feelings then, in hindsight I would say I felt distinctly “other” from the perspectives of class, culture, and ethnicity.

JPH: Was there a Cuban or Chinese community in Naples when you were young?

KW: We didn’t know any other Chinese families until my parents became friends with the owners of a Chinese restaurant that opened a few years after we had moved to Naples. There weren’t many Cubans there either. Fortunately, my mother’s cousins had immigrated to Miami in the early 1970s. We saw them a few times a year, so I became more connected to Cuban culture over time. As more family and friends moved to Miami, my mother’s network grew, but the rhythm of the Cuban community in Miami was different from the rhythm of our life in Naples. For example, we didn’t go to mass or have large family gatherings for Christmas, Thanksgiving, or Easter. My sisters and I didn’t have quinceañeras, nor did we grow up speaking either Spanish or Chinese.[2]

JPH: Which languages did you speak at home?

KW: We spoke English at home because my parents didn’t speak each other’s first languages. Although my mother spoke Spanish to us, we’d reply in English. Eventually I became more competent in Spanish, although not perfectly fluent. When I expressed interest in learning Chinese as a teenager, my father attempted to teach me but I found it too difficult to learn a tonal language. Many years later I studied Mandarin, which my father didn’t speak, so Mandarin became another language barrier.

JPH: What did your father communicate to you about Chinese culture and his background while you were growing up? How did he engage you in his past?

KW: My parents were very proud of their respective cultures and encouraged us to learn about them. My father regularly recounted such historic Chinese achievements as the Great Wall, the inventions of the printing press and gunpowder, and so forth. Bedtime tales ranged from variations on the Monkey King adventures to stories about growing up in China. Because we didn’t have Chinese relatives nearby, I became extremely curious about the world my father painted with his stories. I wanted to know about China’s art, history, and religious traditions.

Fig. 2. Katarina Wong, Fingerprint Project: Murmuration Unfolding, 2017, wax cast molds, sumi ink, and powdered graphite, dimensions variable, courtesy of the artist. Installation view in Circles and Circuits I: History and Art of the Chinese Caribbean Diaspora. Photo by Ian Byers-Gamber.

JPH: Let’s talk about your first trip to Cuba in 1979 when you were thirteen. Why did your family decide to go there?

KW: My mother wanted us to meet our family, but in particular she wanted us to visit our grandfather, Antonio Capin, who was dying from advanced multiple sclerosis. After enlisting her state senator to help her obtain special permission to travel to Cuba, we were finally able to be reunited with her side of the family, after only hearing stories about them. We flew into Havana, met the family there, and then went on to Mantua, my mother’s hometown in the province of Pinar del Río.

JPH: At what point during your subsequent trips to Cuba did you learn about the Chinese diaspora?

KW: Although I had been going to Cuba regularly with my mother since the early 1990s, it wasn’t until the mid to late 1990s that I heard about the historical Chinese diaspora in Cuba, as well as Chinatown in Havana.

JPH: When did you visit Chinatown?

KW: I visited Chinatown in 1998 and realized for the first time there were other Chinese Cubans like myself.

JPH: How did that trip affect your view of your Chinese Cuban identity?

KW: Prior to that trip, I had categorized my experiences as distinctly “Cuban” or “Chinese” or “American.” For example, visiting my relatives in Miami was a “Cuban” experience. Eating dim sum with my dad was a “Chinese” experience. Going to the mall, “American.” After visiting Chinatown in Havana, however, I started thinking of my identity in a different light. I realized that my cultural and ethnic lineages are intertwined. I see the world as uniquely shaped by the commingling of these three prominent cultures.

JPH: The 1998 trip seems to have been transformative regarding your assimilation of your Cuban, Chinese, and American roots.

KW: Very much so.

JPH: How did your Chinese heritage inform your art?

KW: While I was getting my MFA from the University of Maryland at College Park in the early 1990s, my father suggested we study traditional Chinese brush painting together. For a year or so, we took classes together during my trips home to Florida. My father, who had worked as a mechanical illustrator, was a talented painter, and when he was younger he enjoyed painting in his spare time. He studied Western painting, but as he got older he evidently wanted to connect with his Chinese roots and culture.

Fig. 3. (left) Katarina Wong, Lechon: Landscape, 2014, ceramic, (glazed cast clay slip) 11 in. x 10 in. x 15 in.

Fig. 4. (top right) Katarina Wong, Lechon: Landscape (detail).

Fig. 5. (bottom right) Katarina Wong, Lechon: Lotus Field, 2014, ceramic (glazed cast clay slip), 7 in. x 13.5 in. x 11 in.

Photos: Courtesy of the artist.

Looking back, studying traditional Chinese brush painting with my father was one of my most important personal and artistic experiences. I learned to handle ink and watercolor through repetition, through painstaking, sometimes mind-numbing repetition, copying the forms and shapes our teacher showed us. The process of learning to paint this way wasn’t about having a creative vision; it was about understanding both the potential and the limitations of the ink medium.

I love the ink’s blackness, as well as its sheen. Because my father and I took classes together, I had the rare experience of being a beginner with him. Each time I pick up a bamboo brush and ink, I recall that time with him, as well as the excitement and frustration of starting something new. Painting with ink also connects me to the history of Chinese ink painting—although I can’t compare my use of the medium with the great Chinese painting masters like Ni Zan, Liang Kai, Wang Mian, and Shitao!

JPH: In 1998 you not only visited Chinatown, but you were also enrolled in the Harvard Divinity School for a Master of Theological Studies. How did those studies affect your work?

KW: At Harvard I focused on Buddhism, and was particularly interested in how religion and culture influence each other. For example, while Buddhists share core beliefs, their religious texts and practices can vary widely from country to country. I also realized that some of the questions I investigated in my studies were related to my sense of identity. For example, I wondered how everyday life influences one’s identity, religiously or otherwise? How do I understand my unique experiences within broader cultural contexts? When does a culture or a religion become part of my essence versus merely an appropriation?

Through this line of questioning, I was drawn to the Buddhist epistemological doctrine of Pratityasamutpada or dependent origination, which can be understood as “the notion that everything comes into existence in dependence on something else,”[[3] therefore asking if everything might be intrinsically interconnected? Things that may appear permanent, stable, or objectively real are illusions.[4] I understand this doctrine to mean that what we perceive as objective reality is actually a phenomenon we are constantly co-creating together.

JPH: How did the concept of “dependent origination” evolve in your work?

KW: After graduating I returned to my studio and continued thinking about it. Was this explanation of the world a concept I could believe in? Are we as interconnected as this concept would suggest? I began thinking of the ways my life is interconnected and co-created with others. In particular, I started to see a strong connection between my memories and the shaping of my identity. I came to realize that I’m not the only keeper of my memories. Others—friends, family, acquaintances—also hold memories of our shared experiences, and by extension, parts of my identity. Through memory we preserve parts of each other, and I started to see reality—or at least the construction of identity—as a co- creative act.

I wanted to make work that was literally dependent on people I knew. Therefore, I started thinking about migrations, of interwoven cultures. These were ideas I developed in The Fingerprint Project beginning in 2001. (Fig. 1)

JPH: For the exhibition Circles and Circuits, you created a new site-specific installation from the series titled Fingerprint Project: Murmuration Unfolding at the California African American Museum in Los Angeles. Let’s talk about the series and your process.

KW: This ongoing series of installations is based on the migratory patterns of animals. Each installation is made up of hundreds of cast wax fingerprints. First I make molds of people’s fingerprints using alginate, the same material dentists use to make dental molds. Then I tint melted beeswax with powdered graphite to create a spectrum of grays, ranging from white to black. I pour the tinted wax into the molds and place straight pins into them while they harden. Once they are hard, each wax cast is ready to be mounted directly onto the wall.

I paint a light blue field on the wall and pin the cast fingerprints in migratory-like patterns based on my preparatory sketches. Once completed, I arrange the overhead lighting to cast overlapping shadows and paint those shadows on the wall using varying shades of ink. Finally, I add touches of powdered graphite to give additional layers of shadows. The overall effect creates an ambiguous image, where it is difficult to tell what is painted directly on the wall and what hovers above it.

JPH: Your work changed radically in 2009 with the unexpected death of your father. How did your stylistic forms, concepts, and materials shift as a result of this experience?

KW: After my father died, I stopped working for several months. Previously, I had been making colorful, large-scale abstract paintings that looked like bursts or spirals of energy. After his death I couldn’t stand working with color, so I put the paint away and reached for the ink. Working on a smaller, more intimate scale, I flung ink against paper or board, and then—as if looking at a DIY Rorschach test—noticed images that resembled faces, animals, bodies, and body parts merging with (and emerging from) one another. As I continued working, I realized that the metamorphosing images—alternately frightening, agonizing, humorous, or lewd—mirrored my emotional state of grief.

Fig. 6. Katarina Wong, Dos Conejos en Azul y Blanco, 2015, glazed ceramic, bottom rabbit: 5 in. x 16.5 in. x 11 in., top rabbit: 3.75 in. x 16.5 in. x 9.25 in, Courtesy of the artist.

JPH: How did these ink paintings eventually lead to your ceramic work?

KW: I became interested in creating sculptures of some of the recurring animals from the ink paintings so that I could feel them in my hand. I started “sketching” animals by using paper clay (read, non-fired) to quickly make the forms. When I decided to use a more durable material, I hired a ceramic artist who taught me how to hand-build clay. Eventually I learned to make plaster molds to cast clay. Those techniques opened up new possibilities for my ceramic sculpture.

JPH: How did your new ceramic sculpture subsequently evolve?

KW: I became interested in making multiples cast from a single mold, and then altering them so that each one would be unique. I often explore ideas through making multiples.

JPH: The Lechon and Conejos series resulted from learning this technique, correct?

KW: Yes, they did.

JPH: What is the iconographic significance of the pig and the rabbit?

KW: They are relevant to my experiences in Cuba, as many of my Cuban relatives raised these animals for food. It was shocking to play with rabbits and pigs in my grandparent’s backyard in the morning, and then eat them for dinner that evening. I learned firsthand that sometimes animals are nurtured and then killed to sustain us.

Many years later, in December 2013, I attended a family gathering where they slaughtered a pig for the upcoming holidays. I witnessed how pigs are central to the lifeline of a community, especially in a small town like Mantua. The experience made me think about the role the pig plays in Chinese culture, where it is raised for sustenance and is a symbol of ignorance in Buddhism. When I returned to the States, I decided to make the sculptures of the Lechon series based on those relationships.

JPH: Why have you decided to use Spanish titles for the Lechon and Conejos series?

KW: The sculptures are painted in a blue and white palette that refers to Ming dynasty export porcelain, and feature traditional Chinese imagery—lotuses, orchids, landscapes. However, I didn’t want the sculptural work to refer exclusively to my Chinese heritage, so I chose Spanish titles to signify the hybridity of my background.

JPH: Could you elaborate on the imagery of these sculptures, and what inspired them?

KW: One of the books I frequently refer to is the Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting, the Shanghai edition from 1887–88.[5] As the title suggests, it’s a manual for students learning to paint people, architecture, animals, plants, flowers, rocks, mountains, and water. I base my imagery on these studies as a way of underscoring the importance of being in a constant state of beginning. I use traditional Chinese brushes to paint the blue underglaze, which I then cover with a clear, crackled glaze. In attempting to expand the ways I create cross-cultural form and content, I also try to approach each work with the beginner’s sense of freshness and excitement.

Although the image that encircles Lechon: Landscape (Fig. 3, 4) looks like a traditional Chinese landscape, I was actually thinking about the mogotes (steep hills) near Mantua that happen to resemble those from the Chinese countryside. Lechon: Lotus Field (Fig. 5) depicts a pig’s head with lotus flowers and buds. In Buddhism, the lotus—a symbol of purity—grows in murky water, from which the beautiful, fragrant flower sprouts. The lotus is a metaphor for how we can cultivate beauty and virtue from the muck and mud of our lives.

I’m also inspired by classical paintings such as Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin’s Still Life with Two Rabbits (1750). The falling orchids in Dos Conejos en Azul y Blanco (Two Rabbits in Blue and White) (Fig. 6) are taken from studies in the Mustard Seed Garden. However, they also refer to the orchids that grow profusely in my family’s garden, where the rabbits I played with as a child were raised. My work originates from deeply personal experiences, but my intention is to suggest the ways we all constantly negotiate our own experiences of culture, ethnicity, and class. I try to understand my Cuban, Chinese, and American heritage in ways that enable me to “float between contrary equilibriums,” as Federico García Lorca writes in “Poema doble del lago Edén.”[6 ]

Notes

1. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 restricted Chinese labor immigration to the US until the law was repealed in 1943 by the Magnuson Act, which still only allowed 105 Chinese immigrants per year to enter. With the Immigration Act of 1965 those limits were lifted, and for the first time in eighty years Chinese immigration resumed in larger numbers. http://ocp.hul.harvard. edu/immigration/exclusion.html.

2. Similar to a “sweet sixteen” in the US, the quinceañera celebrates a girl’s fifteenth birthday and passage into young womanhood.

3. Donald S. Lopez, The Story of Buddhism: A Concise Guide to Its History and Teachings (New York: Harper Collins, 2001), 29.

4. Peter Harvey, Buddhism (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2001), 242–244.

5. The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting. Edited and Translated by Mai-Mai Sze. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1978.

6. Federico García Lorca, Poet in New York: A Bilingual Edition, edited and introduced by Christopher Maurer, translated by Greg Simon and Steven F. White (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998), 76–79.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Harvey, Peter. Buddhism. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2001.

Lopez, Donald S. The Story of Buddhism: A Concise Guide to Its History and Teachings. New York:

Harper Collins, 2001.

Lorca, Federico García. Poet in New York: A Bilingual Edition. Edited and introduced by Christopher Maurer, translated by Greg Simon and Steven F. White. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998.

The Mustard Seed Garden Manual of Painting. Edited and translated by Mai-Mai Sze. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1978.

Herzberg essay, “Past – Present: Conversations with María Lau and Katarina Wong,” was published in Circles and Circuits: Chinese Caribbean Art (pp. 180-195). Editor and Co-curator Alexandra Chang, Asian/Pacific/American Institute at New York University. Co-Curator: Steve Y. Wong, Chinese American Museum. Los Angeles: Chinese American Museum and California African American Museum, 2017 (Duke University Press, distribution). Published with the assistance of the Getty Foundation ISBN: 978-0-9987451-0-7. Copyright © 2018 Chinese American Museum.

Front Cover: María Magdalena Campos-Pons, “Finding Balance” (detail), 2015

Artwork and photos © Mariá Lau (Figs. 1, p. 178; 2, p. 182; 4, p. 184).

Artwork and photos © Katarina Wong (Figs. 2, p. 188; 4, 5, 6, pp. 190).

Photos @ Ian Byers-Gamber (Figs. 3, pp. 183; 1, p. 186)

Artists websites:

https://www.katarinawong.com/

http://www.marialau.com/